ISSUE 2 January 2015

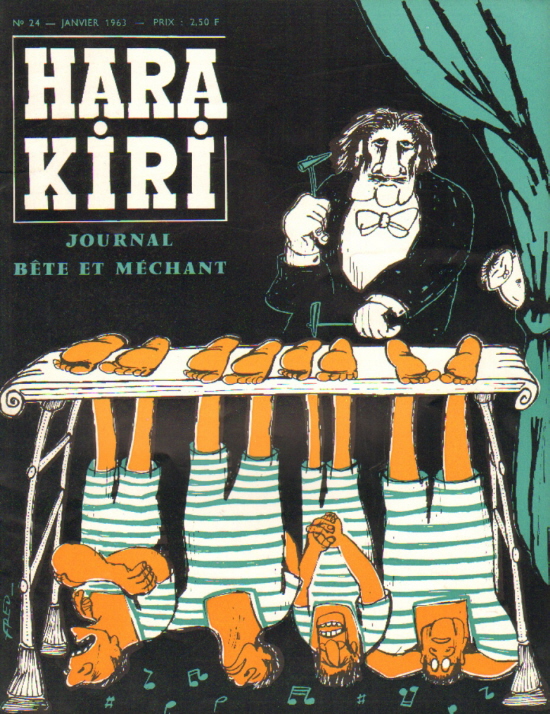

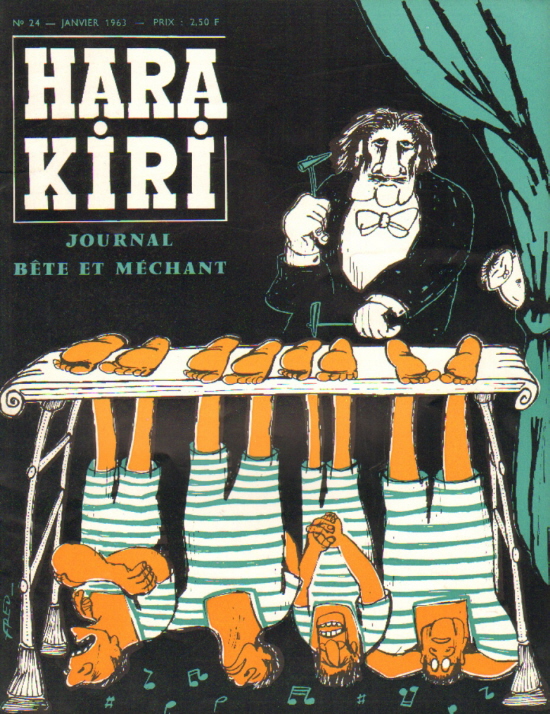

A SHORT SURVEY OF GRAPHIC SATIRE - 1. HARA KIRI

|

Hara Kiri, a predecessor to Charlie Hebdo, ran from 1960 to 1989. Its history is covered on an excellent website at http://www.harakiri-choron.com/index.php?lng=fr from which this extract is taken. It was scurrilous and obscene and Madame de Gaulle didn’t like it. But it wasn’t particularly political. Its initial targets were the strait-laced prudery and inhibitions of the Fifth Republic in the 1960s. The account mentions the change in attitude after 1968 when a more radically orientated rebellion followed the May events. Hara Kiri became marginalised and even during the period covered by this extract we see the emergence of a new voice Hara Kiri Hebdo. Yes, the comrades have a point in their driven desire to institute the revolutionary program but I can’t help having a soft spot for the anarchic obscenity of HK (Viz might be considered a pale English cousin – but more of that in another issue) and I still recall the shock of seeing in a shop window in Lyon the cover of issue 162 March 1975 exhorting job seekers to get a shave. Could it have appeared in UK in 1975? I doubt it. In France they do things differently. A PARTIAL HISTORY OF HARA KIRI Hara-Kiri cannot be considered a political journal for several reasons. Firstly, it didn’t want to be dependent on the vicissitudes of the news and secondly since it was a monthly it took no great interest in current affairs. Any newspaper cannot, however, be timeless. Hara Kiri was founded less than two years after the installation of the Fifth Republic. It passed through the mid-1960s under the Presidency of General de Gaulle. The masthead of the journal "stupid and malicious" avoids concern with government departmental feuds or the result of any referendum. Those young people aimed higher: it is Gaullist society as a whole which must be the object of their attack. Hara-Kiri was unleashed against the traditional symbols of authority, i.e. the church, the army and the police, just as, sixty years ago, was the monthly anarchist L'assiette du beurre. In addition, Cavanna and his crew confronted the modern form of alienation of the masses: the consumer society. Advertising, described as a "thieving whore" by Cavanna, is one of the principal targets. “Advertising takes us for idiots, advertising produces idiots”, proclaims Hara-Kiri. Marketing ‘demagoguery flatters the gullible' The magazine invented parody advertising. Washing powder, household appliances and cars, all products of the consumerist civilization are pushed through the mincer of humour. Legend has it that Hara-Kiri always refused to allow advertising in its columns. In fact, Bernier, with the agreement of the editorial board, wanted to take advantage of this source of funding. They even created an advertising agency, Snob advertising, whose creative team are Hara Kiri members. But it didn't last long. After the great couturier Renoma bought space, the newspaper published a photograph of Hitler and Goering, with this caption: "why Hitler and Goering were also chic? Because they dressed at Renoma! " This caused such a stir among the former deportees that Hara-Kiri abandoned all advertising parodies. In the consumer society of the sixties, sex also became a market. Hara-Kiri dealt with eroticism with irreverent humour. It didn’t seek to demystify female body, but, on the contrary, liked to show naked women in the most grotesque situations. The emergence of eroticism in Hara-Kiri was very gradual, like the general evolution of morals. At first the journal had no drawing or photograph of naked woman. Little by little, as pointed out in Jean-Marc Parisis, “pages start to feel slightly fleshy”. A threshold was crossed in November 1963. After that issue, Hara-Kiri satirised the eroticism of the modern-man magazine. Gradually young women revealed more and more their bodies. There was a world of difference between the beginning of the sixties, where you can sometimes glimpse a leg or a breast, and the end of the decade, where some photographs show completely naked women. Sex was also a theme for some cartoonists of Hara-Kiri, including Wolinski. Cavanna remembers he stopped drawing naked women during editorial meetings: "those shameless women who laughingly dangle appendages from all orifices." What was a private obsession became a public obsession after Jean-Jacques Pauvert published “That’s All I think About” just before May 68. Finally, Hara-Kiri was ruthless towards the popular press of the time. Journals such as Nous Deux or Confidences were filled with cheesy photonovels. In March 1961, Cavanna embraced this format in 'Grocula against Frank Einstein'. The employees of the newspaper play the parts. Bernier was thus a "photonovels" type section, entitled "Professor Choron Answers Your Questions”. With the fake advertisements, unbridled eroticism and "demented photonovels" Hara-Kiri burned into the collective memory. These three examples show how HK wished to expose the celebrity culture of television and sport. Wolinski insisted on the deep divide between the spirit of Hara-Kiri and its sociocultural environment: “The Sixties made us feel repressed. One choked under the taboos”. Bernier confirmed this feeling and spoke about how inhibited France was in those days. Considering the position of employees of Hara-Kiri in Gaullist France, Wolinski likened it "to the kids in a high school with a harsh headmaster". Freedom, the insolence and the irreverence of the journal "stupid and malicious" were, indeed, very quickly censored. From July 18, 1961, a few days after the release on the newsstand of the tenth issue, the Official Journal of the French Republic prohibited Hara-Kiri from display and sale to minors of 18 years, and, by implication, from distribution. Ministerial constraint used law 49-956 of 16 July 1949, as amended on December 23, 1958, on the protection of children and youth. The 1949 Act was exclusively designed publications intended for children and adolescents. It had established a Commission for supervision and control, to check if these newspapers were not showing values “likely to demoralize the children and youth", such as lying, thieving, laziness, hatred, etc. Order n° 58 - December 23, 1958 1298 - issued two days after the election of General de Gaulle - significantly hardened the 1949 Act: section 14 was amended so that any publication could be banned from display, sale to minors of 18 years, and also distribution, if they presented "a danger to youth because it is licentious or pornographic.” . Under the guise of protecting youth, this order actually helped the Gaullist power to control the press. Hara-Kiri was arbitrarily pronounced "licentious" and "pornographic" by the Commission for supervision and control of publications in childhood and adolescence. Bernier and Cavanna, did not expect such an outocome. They agitated to lift the ban. They went to place Beauvau, then place Vendôme, where the Control Board of the Department of Justice sat. The secretary of this Committee, Mr. Morelli, justified the ban on the newspaper. Through specific examples, he accused Hara-Kiri of disrespect towards the elderly, mothers and children. Topor, Fred, Wolinski, and Gébé drawings were considered to be unhealthy... Cavanna and Bernier discovered with amazement the gap between the absolute freedom of Hara-Kiri and narrow-mindedness of this magistrate, a representative of a France still in a straitjacket. In an attempt to fill the financial chasm created by the prohibition, Bernier ran it on a shoestring. Its peddlers sold it illegally in the provinces. He founded a small newspaper, the Playboy of Paris, which was sold only by hand on the streets. Without the income from Hara-Kiri, some members of the team joined other newspapers. Cabu found refuge in Pilot, a weekly based in Goscinny. Six months later, the Ministry of the Interior withdrew the prohibition. Hara-Kiri became a more polished and more conventional journal. For a while it became more circumspect, fearing a new censorship: "those bastards had stifled our enthusiasm", fumed Bernier. In May 1966, Hara-Kiri was banned again under the 1949 Act, amended 1958. However, the Committee on control and monitoring was not, the culprit. It came directly from the place Beauvau, or even of the wife of General Charles de Gaulle... The company's financial situation became untenable. Hara-Kiri left rue Choron, with rent in arrears, and ended up at rue Grande-Truanderie, near Les Halles. Later it was based near rue Choron, at 35, rue Montholon. They produced the single issue of a small newspaper similar to the Playboy of Paris, Am-Stram-Gram, consisting entirely of drawings by Reiser. The latter was, however, forced to work elsewhere to earn a living; He wound up with Gébé, drawing for Pilot. Bernier, strangled by his creditors and threatened by bailiffs, managed to avoid liquidation. He even got his creditors to agree on a plan for the next eight years. With the help of Cavanna and Wolinski, Bernier was able eventually to persuade officials of the place Beauvau to lift the ban. A ministerial order dated November 25, 1966 authorized the re-publication of Hara-Kiri. After seven months of absence, the monthly found a place on the newsstands the following January but its sales declined significantly from 250,000 to 80,000 – 100,000. Many newsagents refused to sell it. The legal settlement was consequently very difficult to enforce. In this last third of the Sixties, Hara-Kiri appeared to be in limbo, especially as the team was slow to reform. There were newcomers like Delfeil de Ton and Pellaert, but stalwarts like Gébé and Cabu, stayed at Pilot. Since it was not a political journal it would be an exaggeration to consider Hara-Kiri as a key driver of the events of May 68. It did, however, participate in shaking up France in the 1960s, which was still very traditional, even archaic. "It is true that Hara-Kiri started a little fire”, said Georges Bernier. He was, moreover, convinced that the soixante huitards were diehard readers of Hara-Kiri and that, without knowing it, the stupid and malicious journal played a role in the cultural and intellectual life of those young undergraduates. 35 rue Montholon became a great breeding ground for many students who were looking for slogans: "I have seen kids queue up to do special numbers of Hara-Kiri for their school. They were crying, begging drawings by Reiser and Wolinski... It was then I realised its importance". In addition, certain employees of Hara-Kiri participated actively in the events of May. Wolinski was, without doubt, the most active: he signed his first political cartoons for the newspaper Action, founded by one of the main animators of the March 22 movement, Jean Schalit, then collaborated with Sine, on the anti-Gaullist journal L’Enragé . Other cartoonists of Hara-Kiri also collaborated: Gébé, Cabu and Reiser. In addition, Wolinski, who then joined the "leftist" movement, actually played a first version of his play, I Don't Want To Die An Idiot at the Berlioz University before an audience of students on May 4, 1968. But if Bernier was excited about May 68 it was for economic reasons rather than political - the general strike in the banking sector allowed him to delay paying his creditors! Like a good anarchist, he was fascinated by the disorder and heckling then prevailing in Paris. The case of Reiser is probably the most complex. Out of friendship for Jean Schalit, whom he knew on the Almanach Vermot, he participated in the first issue of the newspaper Action, but did only two drawings for Enragé. He was not seen on the demonstrations or in amphitheatres. Reiser, son of the people, was, in fact, "shocked by these revolutionary sons of the bourgeoisie". Cavanna played no role in the events of May 68; he was undergoing surgery. Eight months after the 'events' of May the first issue of Hara-Kiri Hebdo appeared. This wasn’t by chance: 68 had created a demand for a magazine more "committed" than Hara-Kiri. The 68ers were no longer satisfied with its lack of politics. It was, as the biographer of Reiser, Jean-Marc Parisis put it: "a spirit of serious challenge has emerged. The absurd and grimacing Hara-Kiri gospel needed more bite. It could even be reactionary. Hara-Kiri displayed a nihilism too shallow for the spirit of the future.” A year and a half after the launch of Hara-Kiri Hebdo, Cavanna, editor of the new journal, left as the editor in chief of the monthly Hara-Kiri. Overwhelmed by work, he entrusted this post to Gébé, his companion of the early days. The first phase of the history of the monthly ends in the sixties. This was a difficult time for the contributors: they often lacked confidence in themselves, their pay was low, the threat of a ban hovered constantly over their heads. Paradoxically, it was also perhaps the the journal's strongest period. In those times of moral Gaullism, Hara-Kiri dared to transgress social codes, adopted all forms of parody and upset the grammar of drawn or written humour. Over the next decade, Gébé strived to continue the project but times had changed: the events of May 68 produced a change of attitude. “Stupid and nasty humour became trivialized" In the end, and despite the insolence of “the era of Gébé ", the more provocative version of Hara-Kiri remains that of the 1960s, simply because it prevailed in a hostile environment.

|