FLOATERS

Martin Espada

978-0-393-54103-8

Norton

reviewed by Alan Dent

Divided into four sections these thirty distinctive poems make up Martin

Espada’s fifteenth collection. The first piece gives the title to the opening

section: Jumping Off The Mystic Tobin Bridge. The bridge spans

more than three kilometres at a height of two hundred and fifty-four feet from

Boston to Chelsea, over the Mystic river. Charles “Chuck” Stuart killed himself

by throwing himself from it on 4th January 1990, the day after his

brother Matthew had told the police Charles murdered his wife in what he had

tried to pass of as a robbery by an African-American. The false allegation

stirred up feeling about racism in Boston. Espada links this well-known,

infamous event to his own crossing of the bridge by taxi, weary of the journey

by bus:

“I hated the 111 bus, sweltering in my suit and tie with the crowd in the

aisle..”

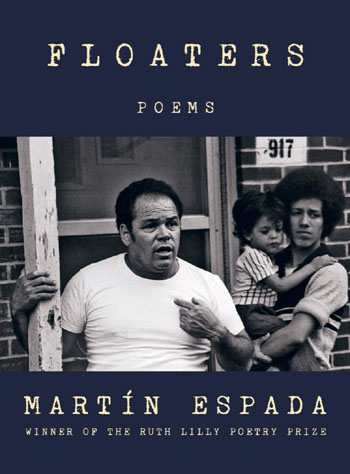

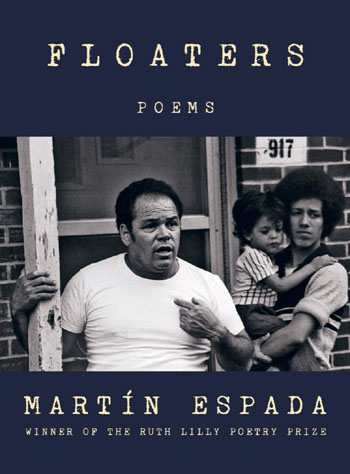

He was working as a legal aid lawyer on behalf of tenants. The cover shows Angel

Luis Jimenez, an evicted mushroom worker photographed

by Espada’s father, Frank. Not one of Espada’s clients, Jiménez’s image

nevertheless represents their plight The driver warned him:

“What the hell you doing here? …There’s a lotta

Josés around here.”

The poem is a clever waltz around the issue of “race” in America:

“The driver, the cops, the landlords, the judges, all wanted us to jump

off the Mystic Tobin Bridge…”

The US Establishment is unable to solve the “race” and immigration problem in

the obvious way: equal rights for all. Locked into the paranoid fear that is the

legacy of the genocide of the First People, slavery and the Jim Crow laws,

ruling American ideology generates the irrational hatred which costs the country

so much. The poem sets the tone for the collection: courageous, honest, outraged

at injustice, on the side of the love and sympathy which make life liveable.

Espada has in common with Fred Voss that he is telling America a truth about

itself it doesn’t want to face. He does so with the skill and discipline of an

experienced, serious writer.

Writing about “race” in the UK tends to be performance poetry, a genre which,

the suggestion is, leaves real poetry, Larkin, Hughes, Heaney, the kind of stuff

you read in quiet libraries and write PhD theses about, untouched. There is in

this something of the condescension which sees people with darker complexions as

entertainment fodder: it’s fine for Louis Armstrong to be a vaudeville

performer, so long as classical music, the really serious stuff, stays white. Of

course, non-white musicians and composers are gaining acceptance and

recognition, but always with an element of self-congratulation: aren’t we white

people wonderful, we will applaud a non-white cello player. We have not yet

arrived where we should be: not noticing what colour a person’s skin may be;

seeing the person not the shade.

Espada is no crowd-pleaser. The second poem bears the collection’s title, a term

used by certain Border Patrol Officers to describe immigrants who drown trying

to cross into the US. The movements of people across the globe are a response to

war, tyranny, injustice, exploitation. The blame goes to the poor and displaced,

while the fault lies with the rich and powerful. The disaffected poor of the

rich countries are easily turned to prejudice against those worse off than

themselves.

“And the dead have names….

Now their names rise off her tongue: Say Oscar y Valeria ..

The photograph of the drowned bodies of Óscar Martínez and his

twenty-three-month old daughter, Valeria, who left San Salvador on 3rd

April 2019 and perished trying to cross the río Bravo between Mexico and the US,

shocked the world, or at least the part of the world which paid attention.

“No one, they say, had ever seen floaters this clean…

Enter their names in the book of names. Say Oscar Alberto Martinez Ramirez;

say Angie Valeria Martinez Avalos..

Espada’s restrained, dignified writing, quietly grants humanity to the

dehumanised.

One of the worst examples of dehumanisation was the Tornillo Tent encampment, a

detention facility for immigrant children in Texas which, during its seven

months of operation, processed (the appropriate term) 6,200 children.

“Praise Tornillo: word for screw in Spanish, word for

jailer in English..”

A soccer ball kicked over the barbed-wire fence by one of the incarcerated

becomes a symbol of escape, freedom, resistance:

“Praise the soccer ball sailing over the barbed-wire fence, white

And black like the moon, yellow like the sun, blue like the world.”

In August 2015 Scott and Steve Leader, Bostonians, urinated on and brutally

wounded Guillermo Rodríguez as he slept outside JFK station, believing him an

illegal immigrant and inspired by the rhetoric of their President, quoted by

Espada as an epigraph:

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re

bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

“His hands fluttered as he spoke, a demagogue’s hands, no blood under the

fingernails, no whiff of urine to scrub away.”

Though Trump was particularly vulgar and demagogic, he stands in a long line of

US President’s whose behaviour violates international law: Eisenhower who

blocked a settlement in Vietnam in 1954 and promoted clandestine terror in

Indonesia; Kennedy, the great liberal, who invaded Vietnam, ordered the use of

napalm and other chemical weapons, established what were effectively

concentration camps for the Vietcong, and brought the world to the brink of

annihilation over Cuba; Johnson who continued the slaughter in Vietnam,

intervened in the Dominican Republic and supported the Israeli occupation of

Gaza and the West Bank; the unspeakable Nixon…..America exports extreme violence

and terror against some of the world’s poorest, and it’s a

fifty-eight-year-old, innocent crop-picker who gets beaten half to death.

Espada’s poem, Not for him the Fiery Lake of the False Prophet, is a

setting straight of the record. It’s typical of the way he can build real

literature from a newspaper article, rooting his poetry in the everyday reality

of denial of humanity which is the experience of those shut out of the

capitalist bonanza:

“We smuggle ourselves across the border of a demagogue’s dreams:

Confederate generals on horseback tumble one by one into

the fiery lake of false prophets;”

He is unique in his willingness to set this unpopular content at the core of his

work. The laurels tend to go to the polite poets, those who assist the

ideological effort by keeping literature clean, steering it towards

contemplation of nature and metaphysical speculation, preventing it from being

the voice of the abused. Yet his poetry never descends to rhetoric. He writes

poetically about Mexicans being urinated on and battered as naturally as

Wordsworth did about daffodils. His achievement is great: he has virtually

created a genre. Posterity will judge him the poet who expanded the bounds of

American literature to embrace what America has always seen as negatively

foreign.

An internationalist by unforced sympathy as well as conviction, in Mazen

Sleeps With His Foot on the Floor, Espada summons the terror of the

civil war in Lebanon ( a response to the PLO’s recognition of Israel and

willingness to forgo violence in return for a Palestinian State):

“Mazen sleeps with his foot on the floor, trailing off the bed.

He does not dream of dancing in Beirut….

Whenever the rockets and bombs shook the house,

Mazen and his brother would jump from the bed and sprint

to the basement.”

Sprinting to the basement is what the world’s poor and powerless must do.

Sacco and Vanzetti were anarchists. I Now Pronounce You Dead is set on

the night of Vanzetti’s execution. The evidence relating to their conviction is

suspect. There is testimony they were involved in the fatal robbery but Vanzetti

didn’t pull the trigger. The essence, however, is that the trial was a farce and

anti-Italian and anti-anarchist prejudice played a large part in their

conviction and execution.

“The walls of Charlestown Prison are gone, to ruin, to dust, to mist.”

The story of Sacco and Vanzetti lives on, men executed because they were

immigrants and radicals, America’s twin nightmares.

“My mother and father met at Vera Scarves, the Brooklyn factory in 1951,”

begins Why I Wait for the Soggy Tarantula of Spinach, about how the

vegetable insult was dropped on his mother’s head as she and Espada’s father

were waiting in a cinema queue:

“This is my inheritance: not the spinach, but the certainty that spinach

is hurtling at my head, or maybe a baby grand piano spinning from the clouds,

and all I can do is wait.”

An accurate evocation of the culture of negative expectation which haunts the

“minorities” in America. “Are you a spic?” Asks the girl in his class

he’s begun to notice. “Yes, I am.” She never spoke to him again.

Much of Espada’s poetry inhabits the loveless public realm, the arena in which

wealth seeks to enforce its rights as democracy fights back; many of his poems

touch on this, the essential battle of our time, the fight against the doctrine

of conquest in pursuit of lucre which gave birth to racism, but they do so that

the best in our nature might prevail:

“You leave me sleeping in the dark. You kiss me and I stir,

fingers in your hair, eyes open unseeing.”

Aubade With Concussion

tells of his wife’s accident on the ice and head injury, relating it to the help

she gave one of her students after her boyfriend’s homicide.

“This is why I say to you,

When you kiss me in my sleep: Don’t go. Don’t go. You have to go.”

Espada’s poetry settles an argument: can literature be political and still

function at the highest level? There is a particular shyness about literature

which openly engages with political questions in the UK, a sense that direct

engagement must diminish the writer’s resources. Except, of course, if the

engagement is on the system’s terms: poems, novels, plays about why there should

be more women billionaires or billionaires of African origin or lesbian

billionaires are more than welcome. Capitalism wants to prove itself beyond

prejudice by permitting a tiny minority of the marginalised a place at the

banquet. Feminism is not about lifting poorly paid, three-job-women out of their

plight but celebrating the go-getters in skirts who have scrambled up the greasy

pole. Who cares if people with darker complexions can’t get jobs if one or two

are highly-remunerated CEOs, barristers, newsreaders? Capitalism is very

experienced at buying off potential radicals. Those who carp are simply guilty

of sour grapes. The truth about socialists is they envy the rich; as if any sane

person would want to emulate Donald Trump.

Against considerable odds, Espada has published an impressive body of work and

in his sixties is still writing at the peak. The poems are all limpidly

beautiful, even when they speak of ugly behaviour and circumstances. They will,

I suspect, introduce British readers to figures they are unfamiliar with: Luis

Garden Acosta, Ramón Emeterio Betances, Arturo Giovannitti, Jack Agüeros: the

book is a history lesson as well as an aesthetic delight.