|

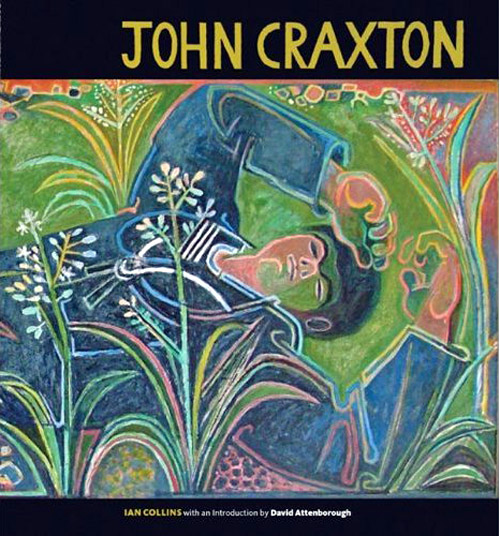

JOHN CRAXTON by Ian Collins Reviewed by Jim Burns

There is in Penguin New Writing 35 (1948) a small selection of photographs under the heading, Portraits of Contemporary British Painters. Eight artists are included: Robert Medley, John Craxton, John Minton, Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde, Keith Vaughan, Lucien Freud, and Leonard Rosoman. There's no doubt that Freud is the one whose reputation prospered and whose work has been internationally acclaimed. Several of the others died relatively early and, it's probably true to say, never achieved their full potential due to a variety of personal circumstances. Minton and Vaughan committed suicide and the two Roberts declined into drink and near-destitution. Freud apart, I suspect that few people, other than those with an interest in British art of the 1940s, will know much about most of the others, though biographies have been written about Minton and Vaughan and the two Roberts. But it's almost 25 years since a major exhibition, A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935-1955 (Barbican, 1987) and Malcolm Yorke's book, The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic artists and their times (Constable, 1988), drew attention to their work. John Craxton appears in Yorke's book and was prominently displayed in the Barbican show. And he survived until he was 87 and died in 2009, perhaps because, while always taking his art seriously, he tended to believe that "life is more important than art," and he spent a lot of time indulging his liking for food, wine, travel, conversation, and the like. There have been suggestions that he spent too much time on these things with the result that his work suffered. Craxton was born in 1922 in London to well-off parents who had artistic connections (his father was a pianist, musicologist, and Royal Academy of Music professor and his mother the daughter of an art publisher). Ian Collins describes their home as "a chaotic haven" and full of "warm bohemian disorder." Craxton from an early age had an interest in art and after encouragement by the art teacher at one of the schools he attended he had work exhibited at a London gallery when he was 11. When he was 14 he went to Paris where he saw Picasso's Guernica. Years later he said: "There's not a line wasted or out of place. And there was no sense of brushwork; I was already aware of the false admiration of 'beautiful passages of paint.' You shouldn't be aware of the construction. The point is the emotional impact." It's interesting, though, that Craxton doesn't seem to have had any kind of response, emotional or otherwise, to the general situation in Europe at that time. As Collins puts it: "the pain, politics and propaganda of a deeply troubled continent passed him by." One thing becomes clear from the account of Craxton's life: he was always fortunate in the sort of people he knew. His family connections put him in touch with various people in the world of the arts as when his mother persuaded Eric Newton, art critic of the Manchester Guardian, to look at his portfolio of drawings. Newton suggested that he apply to the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, but he was turned down because he was considered too young to look at nude models. A friend then persuaded him to go to Paris where the restriction didn't apply. In Paris he was befriended by a Russian family whose daughter had been a visitor to his parent's home in London. Jacques Milkina was a portrait painter and he encouraged Craxton to focus on "the crucial role of drawing and the importance of getting the colour harmonies right in ensuing paintings." By the time Craxton returned to London war clouds were gathering, though again he doesn't appear to have paid too much attention to events outside his own sphere of activities. He enrolled for drawing classes at the Westminster and Central art schools, and accompanied a family friend on field trips to country churches. Drawings from this period show him to be influenced by Paul Nash and "depicting dead, split and toppled trees." And there's a pen and ink illustration of the ruins of Knowlton Church, a place Craxton described as "a set for an M.R.James ghost story." It was in the early-1940s that Craxton met Peter Watson, who was to play a significant role in his life for some years. Watson, a wealthy patron of the arts, was "a collector of beautiful things and brilliant young men, and was the perfect connector for John." He showed him drawings by Samuel-Palmer and Craxton "took these revelatory images as touchstones for his own times and nature." A comparison of Palmer's "Valley thick with corn" from 1825 with Craxton's "Poet in Landscape" from 1941, both reproduced in the book, shows how much he was influenced by the earlier artist. He had never heard of Palmer before seeing the drawings Peter Watson had but knew at once that he had encountered someone special. It's relevant to note that he was also deeply involved with William Blake's work, both poetry and painting. Craxton was faced with conscription in 1941 but was eventually rejected for military service. His 1942 "Dreamer in Landscape," has a man closing his eyes and "blotting out a claustrophobic world of twisted and tortured trees and rampant foliage eerily lit by a sickle moon." It's not hard to accept that it represented Craxton's attempts to escape from the ugly wartime world around him. He later said that "Poet in Landscape" and "Dreamer in Landscape" were derived from Blake and Palmer and were "my means of escape and a sort of self-protection...I wanted to safeguard a world of private mystery and I was drawn to the idea of bucolic calm as a kind of refuge." Both were illustrated in Horizon, a significant publication at that time, and helped to focus attention on Craxton. He may have been trying to stand aside from a London dominated by the effects of war, but being someone never averse to socialising he frequented the pubs and clubs of Soho, mixing with Colquhoun and MacBryde and becoming friendly with Lucien Freud, though they eventually fell out. But for a time they shared a studio, thanks to Peter Watson, and Craxton did say that his time with Freud had its advantages: "He made me scrutinise. I gave him confidence. We respected our diversity. And nobody bothered us - we could just get on and paint." A meeting with Graham Sutherland also had an effect, as did an encounter with John Piper. Ian Collins states: "John Craxton greatly admired the way in which Piper's modernist sensibility had been mobilised from abstraction to record an architectural heritage menaced or destroyed by war." Other factors were at work, with Craxton reflecting some aspects of surrealism so that he was thought ideal to illustrate a book of poems by Ruthven Todd, a poet associated with the "New Apocalypse" group. Craxton's "private world of mystery and allegory" was not exactly surrealistic but neither was Todd's poetry. Craxton said of wartime London: "Everything was narrowed down to practically nothing. In Soho there was the French pub and the Swiss House - which I liked because they were talking pubs - and the Golden Lion where sailors were picked up." He noted that a few galleries were still open and that he sometimes frequented the Coffee An' which was "a rough house with porno-erotic pictures on the wall and an incredible range of customers: intellectuals, draft dodgers, people looking for a pick up." The war also had a restrictive effect on the supply of art materials available, though Craxton, again thanks to family contacts, managed to get hold of a supply of Ripolin household enamel paint which gave his paintings a brighter colour. The artists that Craxton was mostly associating with have generally been linked to the Neo-Romantic movement. The term had originated in Paris in the 1920s but by the 1940s it was being used to describe "certain members of an otherwise disparate group of British artists tied to the appropriated tag in the 1940s by writer and surrealist artist Robin Ironside. He bagged it for an art that was personal and contrasting with the doctrinaire geometrical abstraction of the 7 & 5 Society under Ben Nicholson. In the rigours of war and its aftermath, the title came to cover a sense across the arts of escape from a world of anxiety into an insular landscape protected by history, myth and fantasy." Craxton was never convinced that Neo-Romantic made sense as a term - "You're either Romantic in spirit or you are not," he said - but he did know Keith Vaughan, John Minton, Michael Ayrton, and others, though he wasn't always necessarily impressed by them. He thought that Ayrton was too full of self-importance and described him as "the last barrage balloon in London that never got taken down." Several of Craxton's lithographs were used in The Poet' s Eye, an anthology edited by Geoffrey Grigson, who also wrote a 1948 monograph, John Craxton; Paintings and Drawings, publication of which was financed by Peter Watson. But there was a problem in the post-war years in that Craxton's work was sometimes said to be "too bright, charming and decorative," perhaps because he was too busy enjoying life to get down to the necessary sustained effort that could result in significant creativity. Wyndham Lewis was of the opinion that he produced "a prettily tinted cocktail that is good but does not quite kick hard enough." The ending of the war allowed Craxton to travel, first of all to the Scilly Isles where, Collins says, "John found valuable resources for a series of dark landscapes already begun in Welsh pictures. Primary yellows, blues, reds and greens against black were taken from the banded colouring of tarred fishing boats and worked into luminous Miro-like compositions." Thanks to Peter Watson he visited Paris and then went to Switzerland where a show of his work had been arranged at a gallery in Zurich. Athens followed, again thanks to Watson's influence, and he was represented in British Council exhibitions alongside Matthew Smith, Graham Sutherland, and Ben Nicholson. He certainly appears to have been something of a Golden Boy in the way that his career was advanced through the well-connected. It was the Mediterranean that was to become Craxton's base for most of the rest of his life. He went to the island of Poros where "he could live cheaply and freely" and gain inspiration from "the intensity of Aegean light." The design and colour in some of his paintings are reminiscent of the work of the ill-fated Christopher Wood. In due course Craxton settled on Crete where he painted pictures of Greek boys and sailors and produced landscapes which utilised "double and triple lines in pigment." They also displayed his liking for Byzantine art. I have to admit that when looking at the examples of Craxton's work from this period I have the feeling that they lean towards the decorative, no matter how pleasant they are in their form and colour. It's a feeling I also experienced when I visited the Craxton exhibition at Tate Britain earlier this year (2011). Ian Collins narrates how a Craxton exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1967 "drew a chilly response from critics - many now in thrall to American abstract expressionism and the cool, satiric gloss of pop art. A journey towards playfulness, sensuality and pattern - and love in a hot climate - was noted and resented." This reaction tied in with Craxton's expulsion from Greece when the military junta came to power. He was suspected of espionage, largely because he liked to frequent sailors' bars where, it was suggested, he was fishing for naval secrets. He then travelled widely to North and East Africa, the Canary Islands, Kenya, Tunisia, Morocco, and Lanzarote. Often in financial difficulties he accepted a commission to decorate a harpsichord for the Scottish Baroque Ensemble and collaborated with a potter on a range of domestic ceramics. Collins refers to his "final fifteen years - when he was often locked in what he called 'procraxtonation' – two vast unresolved paintings, and variants on them, often blocked his easels." He did occasionally have paintings in the Royal Academy summer exhibitions, and when he died in 2009 he was "making some of his best drawings for years, with Greek birds, trees, rocks and ravines in black ink soaring above the Tippex white." Was John Craxton a major artist? The answer has to be "no," though he was often a very good one. His early work reflected the circumstances in which he found himself, with wartime restrictions on movement and freedom of expression shaping his thinking. The later work is usually much more colourful and entertaining to look at, though it sometimes lacks depth. It seems to have lost some of the mystery - the enigmatic quality that he mentioned - when he settled on the Greek islands. Did he fritter away his talent in return for easy living? Someone who knew him said: "He was having fun and living doing what he loved," which sounds like an ideal way to get along and something that most people would settle for. But it's not necessarily a guarantee of achieving anything truly remarkable in the arts. Real achievement may depend on a willingness to give up other things in order to concentrate on essentials. Craxton's art perhaps lost the cutting edge of his early promise when he decided that Greece and hedonism were his priorities. Or it could be that he'd realised that he was never likely to fulfil that promise and so settled for a highly competent but stylised art that would appeal to people with romantic or nostalgic notions about the Mediterranean. Ian Collins has written a book that looks fondly on John Craxton's output as an artist. It is beautifully illustrated and well-documented. And if it may not convince anyone that he was a painter of the first rank it should draw attention to him as someone who was highly-skilled and often produced work that, if not always memorable, was usually pleasurable to look at.

|