THE ‘DEATH’ OF THE LIFE ROOM

An Exhibition at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 8th June

2024 to 12th January 2025

Reviewed by Jim Burns

“By the 1950s, the life room came to represent an outdated and academic

model that for some was hindering innovation”. So says a notice accompanying

this modest exhibition, and elsewhere we are told that “life drawing” no

longer occupies a place in formal art training in Britain. “Life drawing”

refers to the disciplined study of

the human form, male and female, and its representation on the page or the

canvas. It’s worth adding that, prior to being able to copy from a live

model, students were often expected to have spent time working from plaster

casts and other forms of fixed models. I think it’s true to say that before

the 1950s many professional artists would have experienced the rigours of

hours in life rooms painstakingly copying the lines and curves of whatever

was before them. It needs to be said that virtually all of the work on

display is by men. Most women were effectively barred from seeing male

models with little or no clothing until well into the twentieth century.

The benefits of this training can be seen in the portrait of a doctor

holding a dissected leg by Jan Steven van Calcar, a sixteenth century German

born Italian artist noted for his anatomical studies. The detail is

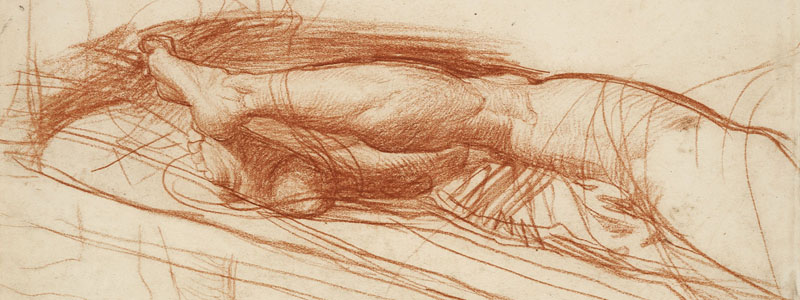

impressive. Jumping ahead to the nineteenth century there is an equally

interesting impression of a man’s legs by the British painter, Alfred George

Stevens. The point to note, I think, is the continuity of close application

to recording what is there that is evident in the work of both artists.

Alphonse Legros was a nineteenth century French painter who became a

naturalised British citizen. His picture of a woman’s head done in red chalk

on paper is striking, as is a portrait by the ill-fated Derwent Lees, an

Australian who was friendly with Augustus John and accompanied him on

sketching trips in Wales.

Towards the end of this survey there are examples of work by modernists such

as Roger Hilton, Reg Butler, Peter Lanyon and Barbara Hepworth, as if to

indicate what happened when artists moved away from the figurative. But I

would guess, though I could be wrong, that they all went through periods of

life drawing and related formal training when they were young. An abstract

sculpture by Hepworth is neatly counterbalanced by her good straightforward

drawing of an embracing couple on a nearby wall.

This is a small but satisfying exhibition with work by Edward Burne-Jones,

Walter Crane, Thomas Rowlandson and others besides those mentioned above.

It’s still possible to argue about what was lost when the life rooms were

closed. Did it lead to self-indulgent art that lacked skill, or did it free

artists to be genuinely more creative?

It’s a question that has still not been satisfactorily answered and

perhaps never will be.