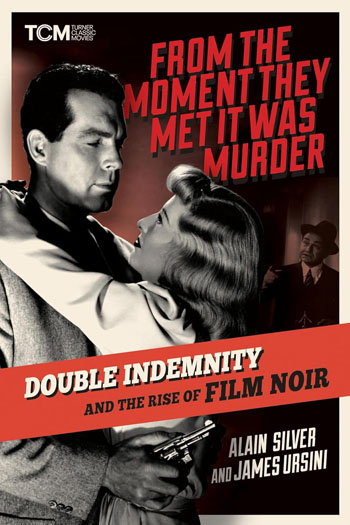

FROM THE MOMENT THEY MET IT WAS MURDER : DOUBLE INDEMNITY

AND THE RISE OF FILM NOIR

By Alain Silver and James Ursini

Running Press. 340 pages. $30. ISBN 978-0-7624-8493-5

Reviewed by Jim Burns

You only need to look at the bibliography in this book to realise that there

is now a whole industry built around the subject of film noir. But what is

film noir? The term was coined by French film critics in the mid-1940s and

they meant it to designate a specific kind of film emerging from the

Hollywood studios of the time. These films had certain characteristics of

“tone and mood” that set them apart from other films, though on the surface

they sometimes seemed to be covering the same ground. It became almost a

convention in films of the 1940s and 1950s to have sleazy settings and

downbeat themes, to the extent

that the definition of film noir incorrectly expanded to include almost any

crime film.

I’m looking at a copy of Spencer

Selby’s Dark City : The Film Noir

(McFarland, Jefferson, 1984) which lists 400 films Selby considers can be

included in the film noir category. I’m not condemning what he’s done –

Dark City has been a constant

reference book for me when tracking down some less well-known productions -

but I think it would be possible to challenge him about quite a few of his

choices. I recently watched Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell in

His Kind of Woman and, while it

had entertainment value, unlike Selby I’d hardly class it as film noir. It

lacked the tensions inherent in a noir tale where the central characters

slide towards disillusionment or death or both. It’s worth adding that

Arthur Lyons’ Death on the Cheap :

The Lost B Movies of Film Noir (Da Capo Press, New York, 2000) has

almost one hundred pages of films, quite a few of which aren’t

covered by Selby’s book,

though again it might be asked if many of them are noir? All noirs may be

melodramas, but not all melodramas are noirs.

Noir was noticeable long before 1940s Hollywood, or Weimar Germany, where

more than a few of the directors – Billy Wilder, Robert Siodmak, Fritz Lang,

among them – started their careers. “You are the deed’s creature”, says De

Flores to Beatrice in Thomas Middleton and William Rowley’s 1622 Jacobean

play, The Changeling, after she

has persuaded him to murder someone she is expected to marry but thinks

unsuitable. She then claims modesty when De Flores comes to demand what he

considers his rightful reward. “Push, you forget your selfe, a woman dipt in

blood and talk of modesty”, he mocks”. It’s

pure noir and we know the deed will lead to their destruction.

So it is in Double indemnity.

Barbara Stanwyck is not the innocent Beatrice wants to be, nor Fred McMurray

devious in the style of De Flores, but they will both become creatures of

the deed. As were the inept lovers who, in 1920s New York, conspired to

murder the woman’s husband, and gave James M.Cain an idea for his novel,

Double Indemnity, published in

1936. Cain had worked as a reporter

in New York and covered the trial and executions of Ruth Snyder and Henry

Judd Gray. The case caused something of a sensation, not just in America but

also in Europe, though it was a fairly routine affair and the couple were

easily identified by the police due to their clumsiness in planning and

carrying out the killing. It’s probably largely remembered now because a

journalist smuggled a camera into the execution chamber and somehow got a

picture of Ruth Snyder strapped into the electric chair. The authors include

it in their book and offer a fairly detailed account of the trial, and its

background, though it’s hard to see how relevant knowing all this is in

context. Cain’s novel has no direct

links to the events that inspired him to write it, and neither has the film.

Leaving that aside, it might seem something of a contradiction to say that

Alain Silver and James Ursini have some interesting things to suggest about

the long-standing tradition of using the main outlines, if not the facts, of

“true crimes”, as the basis for

novels and plays. They cite, as an example, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Mystery

of Marie Roget”, set in Paris but inspired by the 1841 murder of Mary

Cecelia Rogers in New York. There is also Frank Norris’s

McTeague and it would be hard to

overlook Theodore Dreiser’s An

American Tragedy. Both had their beginnings in real-life crimes but

Norris and Dreiser didn’t hold to the facts, and their readers didn’t need

to know what those facts were to enjoy the novels.

Years ago, when I taught a creative writing class, I took a clipping from a

local paper, read it to my students, and suggested it had the basis for a

short story. A couple, he in his twenties, she in her forties, had an

affair, conspired to get rid of her boorish husband, and successfully did

so. The verdict was accidental death and it looked as if they were in the

clear. But the woman discovered that the man was also seeing someone of his

own age, and threatened to go to the police if he didn’t end the

relationship. He didn’t, so she did, and both were arrested, tried, and

sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. It had, to my mind, a noirish touch

about it, though none of the class thought it sufficiently original to make

a good story. But, as I tried to make clear, it isn’t what you do, it’s the

way that you do it.

That’s the point about the film,

Double Indemnity, which essentially has a routine plot. Slick insurance

salesman, Walter Neff, calls at a house on a routine matter of renewing a

policy. The husband is at work so he talks to the glamorous wife, Phyllis

Dietrichson, and is excited when she crosses her legs and brings to his

attention the”honey of anklet” she is wearing. The authors (I suspect Silver

did most of the writing) say that it’s Neff’s “fetish”, the thing that

initially turns him on to Phyllis’s sexuality. There is some verbal sparring

between Walter and Phyllis, but it’s obvious that they are attracted to each

other, if for different reasons. He calls at the house again, making up a

sham excuse, which she easily

sees through, and they’re soon involved in an affair, with its hurried

telephone calls and clandestine meetings in supermarkets and elsewhere.

Phyllis soon takes the lead, probing about life insurance for her husband

and whether there is a way a policy can be taken out without him knowing

about it. Walter rigs it so that the husband signs the appropriate document

without bothering to check what it is. It’s then just a matter of convincing

Walter to go ahead with the plan to kill Phyllis’s husband and collect the

insurance money. So far, so good, though because of the way that the film is

structured, with the wounded Walter recording a confession at the beginning

of the film, we already know

that something must go wrong. His voice-over narrative of how the affair

moved through its different stages holds the film together. The script by

Raymond Chandler and Billy Wilder, who also directed, retains a sharp

down-to-earth tone throughout, in both the voice-over sections and the

action scenes. As in most noir films, some minor characters pop up to add

aspects of the ordinary going on as a background to murder. A small elderly

lady in the supermarket interrupts a guarded conversation between Walter and

Phyllis to ask him to hand her a packet from a top shelf. A simple touch,

but convincing in its routine nature.

One of the factors that is interesting about

Double Indemnity is that neither

of the leading characters could be described as proletarian, a term much in

use when Cain published his book (1936) and when the film is set (1938). The

film was made in 1943 and released in 1944, so “proletarian” was perhaps

less common then? In the film Walter is clearly a successful and well-paid

insurance agent and Phyllis lives in some comfort and doesn’t seem to want

for anything material. They’re a long way from the central characters in

another Cain novel, The Postman

Always Rings Twice, which became a noted film noir. Frank Chambers is a

drifter, conning his way from place to place, and Cora Papadakis the wife of

a Greek owner of a “roadside sandwich joint, like a million others in

California”. But no matter the social class, the situation is the same. A

dissatisfied wife, a husband she doesn’t care for, and a handy young man who

comes in useful when it’s time to get rid of the husband. The authors of

From the Moment They Met it was

Murder refer to “proletarian lovers” when describing Ruth Snyder and

Henry Judd Grey, but they don’t strike me as in that category. More lower

middle-class, though it could be that I’m thinking of “proletarian” too much

in its 1930s political sense, a

time when it mostly indicated the industrial working-class.

I’m touching on topics that aren’t a major part of

From the Moment They Met it was

Murder. Where the economic matters occur it’s usually in terms of the

financing of the film. There is a long chapter, just over sixty pages, which

will satisfy those who want to study the workings of the studio system. I’m

not suggesting that the information this chapter contains is of no

importance. However, I have to be honest and admit that I couldn’t get too

concerned about payments to Mona

Freeman, who doesn’t have a role to play in the completed film. There is,

perhaps, something more relevant to be said about the cost of building a gas

chamber where Neff was supposed to be seen in his final moments (shades of

that photo of Ruth Snyder being executed?), though it was dropped from the

film. Wisely so, seems to have been the general concensus of opinion. It

wasn’t necessary. We know that Neff is at the end of the line, one way or

another. He’s confessed, he’s badly hurt, and the police are on their way.

The subtitle of the book is “and the rise of Film Noir”, and I think this

could have made for a longer discussion than we get. The chapter on what

happened after Double Indemnity

was released in 1944, and proved to be popular with most critics and

certainly with audiences, is mostly taken up with brief accounts of what

some of the key participants in the making of the film moved on to. Billy

Wilder, for example, directed classic films like

The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard,

and

Ace in the Hole. Barbara

Stanwyck was in several films which are usually included in film noir

listings - The

Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The Two Mrs Carrolls,

The File on Thelma Jordan, and

Clash By Night. I’m not

discounting the value of this information, but the section entitled “The

Rise of Film Noir” is allocated just over twelve pages, and would have

benefited from a longer discussion which could have questioned how many noir

films genuinely fit into that category? And how the basic premises of noir,

as pictured in something like Double

Indemnity, were diluted in various ways.

Of course, at the end of the day it might well be asked if it

matters? I doubt that many people watch a film and think, ”is this noir?”,

though a few specialists perhaps like to do that. But, from a personal point

of view, I’d have preferred to read about some obscure noirs instead of how

much people were paid. Yes, money was always of key importance in Hollywood,

but we base our judgement of a film on the finished product we see on the

screen.

I’ve mentioned a few difficulties I had with the book, but taking it as a

whole it has something to offer. It will appeal to Hollywood enthusiasts,

those who can’t get enough about how the studios functioned and the disputes

that occurred. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler didn’t get on too well,

partly due to Chandler’s alcoholism, and Wilder later said that making

The Lost Weekend was inspired by

this, though the film is actually based on Charles Jackson’s 1944 novel of

the same name. Some of the technicalities involved in film-making are

usefully dealt wish. People like the

cameramen, set designers, composers, sound engineers

and others are too often overlooked

when films are discussed. Silver and Ursini do try to give credit where it’s

due. They also rightly draw attention to Edward G.Robinson’s low-key but

essential presence throughout the story.

From the Moment They Met it was Murder

has substantial notes and a good bibliography.

It has photographs and a brisk

writing style that often tries to emulate the kind of prose

found in pulp novels produced in the Forties and Fifties which were

the inspiration for numerous

noirs: “It had rained heavily in Ossining New York that afternoon. The air

was heavy with moisture, as three men braved the chill to stand behind a

stone railing on a second floor balcony and smoke”. It’s obvious that

something is about to happen. Or “Was it dawn? He was shivering. He coughed,

a spasm that twisted his torso”. Who is he and why does he seem to be in

poor condition?. Writing like this might be questioned when used in a

serious study of a key film, but the authors no doubt thought it appropriate

in the circumstances.