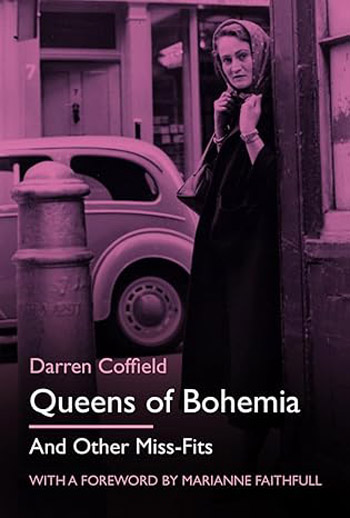

QUEENS OF BOHEMIA AND OTHER MISS-FITS

By Darren Coffield

The History Press. 352 pages. £25. ISBN 978-1-80399-574-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Bohemia? Does it still exist? And, if so, where is it and who are its current

inhabitants? And if it doesn’t exist anymore, except as an idea, a memory, a

dream, then why is it no longer somewhere we can identify and locate in

specific areas where at one time it seemed to flourish. Some would argue

that Soho, Greenwich Village, and Montparnasse are shadows of their former

selves. You might find an advertising executive, a tired businessman, two or

three tourists, or someone from the media propping up a bar, but not many

poets and painters. They’ve been driven out by high rents and commercial

ventures that go against the grain of bohemian living.

It costs a lot to be poor these

days. There’s also the problem that Marianne Faithfull refers to in her

nostalgic introduction to Queens of

Bohemia when she reflects on her experiences in bohemia : “Art was more

intense, purer.....And there was a genuine intellectual bohemia instead of

the hipster-lite culture we have today”.

One thing is for sure, though. If bohemia does still have a definable

existence it’s to be hoped that it’s a better place for women when compared

to the past playgrounds of the artistically-inclined. I’ve read quite a few

accounts of life in the areas referred to in the previous paragraph, and

they might well be summed up by the title of one of them, Floyd Dell’s

Love in Greenwich Village.

There we have it, a man writing

about his time in one of the famous haunts of bohemians. I’m not suggesting

that some women didn’t also produce memoirs

about their days in bohemia, but they weren’t as prevalent as those

by men, and on the whole they were less likely to be too open about their

indiscretions. Someone is sure to refer me to Anais Nin, who didn’t seem to

mind who knew what she did, but she was an exception to the rule that women

stayed in the background in these matters. A man who had a reputation for

seducing a large number of women was seen as “a bit of a lad”, whereas a

woman who liked to sleep around was sure to be given a label as a slut or,

more politely, a nymphomaniac I suspect It’s still that way, even in our

supposed liberated times.

What is noticeable in most acounts is the way in which many women were

treated in bohemia. Darren Coffield’s entertaining, if sometimes disturbing,

book covers a period, roughly 1920 to 1960, and mostly focuses on a

relatively small number of people, wiih a selection of others coming and

going, And all of them functioning in a relatively small area of London,

namely Soho and Fitzrovia. It can be narrowed down even further to a limited

number of pubs, clubs, restaurants, and private houses. There are moments

when the action shifts to Chelsea or “Little Venice” in Paddington, but on

the whole Soho/Fitrovia is where people came together. The title of an

exhibition at the Parkin Gallery in 1973 was “Fitzrovia and the Road to the

York Minster”, with Ruthven Todd (he’s mentioned more than once by Coffield)

acting as guide to the route to be followed to get from the Fitzroy Tavern

in Charlotte Street, across Oxford Street, and down to the York Minster, or

the French as it was better known, in

Dean Street. There were other pubs on the way.

The French is usually associated with its landlord, Gaston, the son of

Victorienne and Victor Berlemont who were Belgians despite the York Minster

being known as The French. It was a popular meeting place for French

servicemen in London during the Second World War. One of the regulars at The

French was the artist Nina Hamnett, though she had also frequented the

Fitzroy Tavern. Coffield doesn’t mention it but in a 1931 novel,

Ragged Banners, by Ethel Mannin

there is a scene in a pub clearly based on the Fitzroy in which there is a

reference to a woman “with glazed eyes, and her tawdry clothes, a ruin of a

woman”. It was obviously a portrait of Hamnett, and it has to be said that

little in Queens of Bohemia helps

to dispel this notion of her as a dirty and dishevelled drunk forever

cadging drinks off anyone she thought likely to pay for them.

I’m not blaming Coffield for the largely negative view of Hamnett that is in

evidence in his book, and he does indicate that she once had a reputation as

a talented painter. But most of the reminiscences of her do tend to stress

how far she had fallen from her glory days in

Paris when she had known Modigliani, Braque, and Picasso. Her

autobiography, Laughing Torso,

originally published in 1932 is worth reading. A second volume,

Is She a Lady?, which came out in

1955, isn’t quite as good, but it does have some drawings from 1954 which

show that she could still apply herself to her work when she chose to. She

died in 1956 when she fell forty feet from an upstairs window. It occurs to

me to suggest that more rounded portraits of her can be found in Denise

Hooker’s Nina Hamnett: Queen of

Bohemia (1986) and Alicia Foster’s

Nina Hamnett (2021).

Hamnett had been a student at the Slade School of Art, and a later

generation of women artists included Elinor Bellingham-Smith and Nicolette

Devas. the sister of Caitlin Thomas, who became famous for being the wife of

the poet, Dylan Thomas, and like him had a penchant for alcohol which caused

both of them to argue, often violently, in public. As for Bellingham-Smith,

she came from a comfortable background and had trained as a ballet dancer

until an injury put paid to her ambitions in that direction. While at the

Slade she met Rodrigo Moynihan. They married and had a son, John, who later

wrote a book, Restless Lives: the

Bohemian World of Rodrigo and Elinor Moynihan (2002) which documents the

ups and downs of their relationship as they established reputations in the

art world. Rodrigo became a successful portrait painter (of Princess

Elizabeth and the then Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, among others), though

he also experimented with “objective abstraction”, while she concentrated

mostly on landscapes.

Both appeared to have had various affairs, with Rodrigo eventually leaving

to live with the artist, Anne Dunn, who previously had an affair with Lucien

Freud and became pregnant by him. Coffield refers to “sleeping with Elinor

Bellingham-Smith” becoming, “ a rite of passage for many young male artists,

such as Michael Andrews”. And to John walking in “on his mother shagging his

school friend”. I have to admit that throughout Queens

of Bohemia the non-stop bed-hopping often left me confused about who was

sleeping with who, especially when I read that Elinor also somehow bedded

the resolutely homosexual John Minton and shortly after “stole” his

boy-friend.

I don’t think Coffield is condoning these activities, just recording them,

and he does say that “growing up in a bohemian household badly affected

Elinor’s son, John”. Elsewhere in his book he mentions the children of other

bohemians, such as the sons of George Barker and Elizabeth Smart who, in

their mother’s absences, were often looked after by the “two Roberts”, the

Scottish painters, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde. Talking about the

Garman sisters, (Mary married the poet Roy Campbell, Kathleen had an affair

with the sculptor Jacob Epstein, and Lorna was the wife of Ernest Wishart,

“the publishing wing of the British Communist Party”), he says: “Kathleen

and her sisters may have pioneered a progressive lifestyle, but their

children paid the price. Like her sisters Kathleen and Lorna, Mary opted out

of taking any responsibility for her children too.....They were feral. Nits

could be seen crawling in their hair, they often went hungry and their

clothes were torn; they were seriously neglected”.

Although Queens of Bohemia

focuses on the women it’s inevitable that it also contains a fair amount of

information about the men, most of who seem to have behaved badly. Augustus

John helped set the style for the “roaring boy” image of a bohemian and

attempted to have sex with any female he encountered. According to Coffield

he was like his friend Eric Gill and saw his own daughters as suitable

objects for his attentions. The list can be extended. Lucian Freud had a

reputation for taking up with any number of women, and ditching them when

someone else came along. When Anne Dunn married Michael Wishart, Coffield

says, “Lucian didn’t attend the wedding “because he felt a bit awkward,

having slept with the bride, the groom, and the groom’s mother”. Coffield

adds, “Despite claiming he was besotted with the beautiful Caroline

Blackwood, Lucien still found time for liaisons with Caryl Chance, Henrietta

Moraes, and the feminist icon, Simone de Beauvoir, whom he’d met at the

Gargoyle”. The latter establishment, located in Dean Street at its corner

with Meard Street, was one of

the drinking clubs favoured by the bohemians.

People pop in and out of Coffield’s story. The old Etonian Robin Cook, who

wrote The Crust on its Uppers,

and, as Derek Raymond, popular crime novels. had a girlfriend named Veronica

Hull. She produced a novel called The

Monkey Puzzle, “which lifted the lid on the philosopher Freddie Ayer’s

sexual activities with his female students....and the ensuing scandal caused

Veronica Hull’s mental breakdown”. The noted critic William Empson and his

wife, Etta, make an appearance, with Empson seemingly encouraging her

affairs with other men: “In his poem, ‘The Wife is Praised’, he seems to

claim many men desire to share their wives with other men and, from here on,

Hetta took male lovers who inevitably became part of the household”.

According to Simon Duval Smith (Hetta’s son by Peter Duval Smith),

“William’s unorthodox views of relationships and sexuality shaped his

literary criticism”. Empson

himself kept active, in more ways than one, and students referred to his

major work, Seven Types of Ambiguity

as more likely, Seven Types of

Infidelity.

Because there is so much about the sexual escapades and general misbehaviour

of the bohemians in this book it’s sometimes easy to overlook the nuggets of

information about forgotten books

and overlooked writers and

artists in its packed pages. Jill Neville’s name crops up and

it reminded me that I met

her at a literary event in, I think, the 1970s. Does anyone now read

her novels? Paul Potts is mentioned more than once, though often in a

similar way to Nina Hamnett. People remember their bad habits and, unkempt

appearances, and forget their past achievements. And to be honest when I saw

him in The French one night he was much like he’s described in

Queens of Bohemia. But I still

think Dante Called You Beatrice,

and a few of his poems, deserve remembering. Bobby Hunt, a one-time student

of the ill=fated artist John Minton, was very much a fixture on the bohemian

scene in the 1950s and was still frequenting the French in the 1970s when I

had a conversation with him about Charlie Parker and the tune, “A Night in

Tunisia”.

The painter Matthew Smith, whose “uniquely turbulent style and

subject-matter of still lives, landscapes, and unhibited nudes” I’ve alway

found of interest, has his place here. Coffield suggets he was less than

fair in his dealings with Mary Keene, his model and mistress, though Malcolm

Yorke, in his 1997 biography of Smith, refers to him bequeathing a large

collection of paintings and other materials to her when he died in 1959.

There are so many others I’d liked to have looked at. Joan Rodker, who

helped organise the Sheffield Peace Congress in 1950 when the Labour

Government banned quite a few of the delegates from entering the country.

David Archer, the well-to-do bookseller who spent all his money supporting

poets, and ended his life poverty-stricken in a doss house.

Not everyone who spent time in bohemia stayed there. Coffield notes that the

actor Norman Bowler, the second husband of Henrietta Moraes, “knew that he

had to leave bohemia to survive”. He did and was soon a “household name on

Brtitish television”. He later said, “Soho in the Fifties became a

myth....Forgotten are the suicides, the attempted suicides, the

spitefulness, the bitterness and the loneliness. But it produced a talented

period in England like no other”.

Queens of Bohemia

is a fascinating book if, like me. you find the chronicles of bohemia of

interest. The booze and the breakups weren’t the whole story, and good work

was done, even if it was only a

part of what was being turned out around the country generally. Coffield’s

concern is mostly with London, but in painting, for example, artists in St

Ives were rightly attracting national and international attention. Bohemia

was alive there, too, and was satirised by the artist Sven Berlin in his

novel, The Dark Monarch. Focusing

on the sex lives and the misbehaviour of artists and writers isn’t the whole

story, and It would be possible to construct a book about bohemia around the

little magazines, small presses, bookshops, poems, and novels linked to it

in one way or another. But it might not attract the kind of attention that

the scandalous usually does.

It’s worth adding a note about Coffield’s approach

to the structure of his book. He builds up his narrative with excerpts from

interviews, memoirs, and other sources, and only inserts his own voice to

provide a linking commentary or offer some additional information. It’s a

form he used succesfully in a previous publication,

Tales From the Colony Room: Soho’s

Lost Bohemia (2020), and it

works just as well in Queens of

Bohemia.There are notes, illustrations, short biographies, and a useful

bibliography.