|

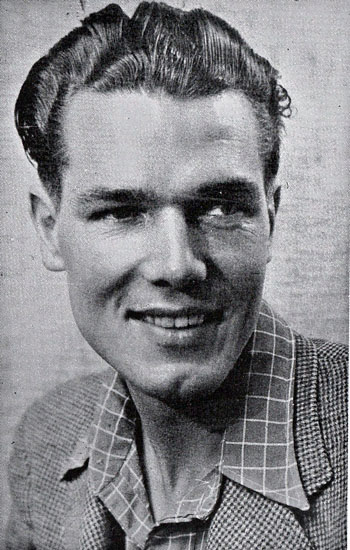

DENYS VAL BAKER AND ST IVES

JIM BURNS

My main purpose in writing this essay about Denys Val Baker is to

direct attention to two novels and half-a-dozen short stories in

which he drew on aspects of the artists’ colony in and around the

one-time, small Cornish fishing town of

He was born in

Val Baker was a conscientious objector during the Second World War,

and seems to have been active around literary

That Val Baker had more than a passing interest in little magazines

was demonstrated by the publication of his first book in 1943.

Titled Little Reviews

1914-1943, it provided a fifty-three page summary of significant

publications in the period concerned. As Val Baker himself pointed

out, it was “an apparently unexplored field” in terms of trying to

document developments and differences in magazine publishing. To

follow up on his small book, Val Baker was chosen to edit an annual

selection of material from current little magazines which continued

from 1943 to 1948. I should add that a glance at a Val Baker

bibliography will show that he was also involved with several other

publications, such as Writing

Today, Modern Short Stories, and

Voyage. As well as

editing, he was also working on his own novels and stories. His

first novel was published in 1945, with two more appearing before

the end of the decade.

Val Baker would easily fit into the bohemian category, but could

never be accused of being non-productive. Once situated in

Val Baker was clearly aware of the presence of artists in

I’ve hopefully managed to impart the idea that he was an established

member of the St Ives artistic community, so was in a position to

observe its personalities, absorb its atmosphere, and create

fictional interpretations of life there. A constant theme

appears to be to indicate that moving to live in

In Val Baker’s novel, A

Journey with Love, published in 1955 (see Bibliographical

Notes), Martin works in an advertising agency but really wants to

abandon commercial work and paint for his own satisfaction. Lesley

in an actress. They decide to quit

It might be worth mentioning that

A Journey with Love was

originally published in the

There are references to St Ives and its colony of artists. Martin

visits a sculptor (probably based on Sven

A second Val Baker novel,

Company of Three, appeared in 1974, though the events it was

partly based on took place in the 1950s. It has some quite obvious

autobiographical elements, as for example in the character of

Stanley, a writer who edits a small, short-story magazine and whose

wife is a potter. They have previously lived in

The weekend develops, with Vivian who is now, as one of his friends

points out, “Drinking like a fish, never eating, never sleeping……”,

and still in love with Nell. It all ends in tragedy when Vivian

drives off in his battered old van after shouting to Stanley, “you

and your swanky new car. Race you to

It would seem that there was an incident like this when the potter

Len Missen was killed and that Val Baker had been present and

driving on the same road as Missen. There doesn’t appear to have

been any evidence that they were racing and, in fact, Val Baker’s

vehicle was in far better condition than Missen’s and a competition

would have been a non-starter. It’s probable that Missen had been

drinking and was driving too fast, anyway. The noteworthy thing

about Company of Three is

that the originals for most of the characters are easily

recognisable.

The two novels referred to seem to be the only ones in which Val

Baker dealt directly with art and artists. But he also wrote several

short stories which revolved around painters and others. In “A Work

of Art”, a writer “discovers” the work of an artist he initially

knows nothing about. His comments on how he reacts to the paintings

are enlightening: “I am a writer, not a painter or an art critic and

no doubt my attitude to painting would be what is called literary,

i.e. rather on the romantic side; indeed, I must confess I did not

now then and have never bothered to ascertain since, exactly what

standards of technical abilities lay behind the painting I now gazed

upon in that gallery window”. It’s the “vivid scattered combinations

– colours and shapes, lines and shadows, sea and land and sky all

concentrated into some cohesive whole –“

that draw his attention to the painting.

He finds out who the artist is, sees more of her work, meets her in

person, and he begins to be attracted to her. But when he realises

that she is probably in love with someone else he starts out on a

campaign to destroy her work, commencing with the paintings by her

that he owns, proceeding to attack canvases hung in galleries, and

finally invading her studio and disfiguring what he finds there. The

story ends in a bizarre way and with the writer aware that whatever

he has done he is still a “superficial observer”. She has told him

at one point that “Words are really inadequate, aren’t they?”, and

it suggests that he will never be able to break through to either

her or her work.

Although Val Baker put the words into the mouth of his fictional

female artist they are actually from an interview with the painter

Margo Mackleberghe that he included in his non-fiction survey of the

creative spirit in

The suggestion that an encounter with artists and their work might

not always be beneficial is also to be found in “Testament of a

Green-Eyed Man”. A young couple move to

The dark side of life in

Mark is an archaeologist and often away on explorations, leaving

Shelley alone. The narrator begins an affair with her, but soon

realises that he’s not her only lover: “She was, in fact, a natural

nymphomaniac, completely self-possessed and totally unconcerned with

anyone’s feelings save her own”. As for Mark, he is seemingly

oblivious to what his wife does, and is obsessed by the Celtic past

that he researches. It’s a “world of primitive, yet cunning people

who lived by different gods, different values”.

He takes the narrator to an area where there is a large flat

stone and says: “Two thousand years ago this place was alive. The

priests came up that path, then they formed around the big stone.

Fires were lit, men carried in the sacrifice. There was the smell of

myrrh and incense. And blood”. When asked what the sacrifice was,

Mark replies, “A woman”.

They throw a party, the theme of which will be everyone dressing up

like Ancient Britons, with the culmination being a celebration at

the old stone and a mock sacrifice. The guests, some of them hooded

like the priests of old, gather around the stone and Shelley lies

down on it. Most of the men had been her lovers at one time or

another. The moon is suddenly hidden by dark clouds, there is a

“wild cry, the like of which none of us had ever heard before”, and

when it’s light enough again to see, Shelley is dead, killed by “the

long sacrificial knife” Mark had discovered on one of his

archeological digs. But who had murdered her?

Women do seem to have had a largely disturbing influence in Val

Baker’s stories, and “The Girl in the Photograph” continues this

idea as an artist and his wife move to live in an old mill. They are

given several old photographs of some of the previous occupiers, and

in one of them can be seen a young woman lurking in the background.

The artist becomes obsessed with the girl, has clearer copies of the

photograph made, and starts to find out more about her. It turns out

that her name was Maeve, she was from

Finding out these basic facts doesn’t satisfy the artist, and in the

end his need to know more and almost will Maeve into life, despite

that she’s been dead many years, not only affects his work, but also

drives a wedge between him and his wife. In a scene where she taunts

him about his feelings for Maeve he assaults her, with the result

that she leaves him. In the end, he’s living in a dream world,

realising that his passion will “consume” him, perhaps to the point

of death. He constantly haunts the cliffs where Maeve was known to

wander: “Or perhaps, and this I think is more likely, she will be

waiting for me out on the wild cliffs, dancing away from me across

giant granite steps, out and out towards the mirror of the sea until

one day, leaping forward to grasp her hand, I shall be lost with her

in some vast eternity”.

It’s something of a relief to turn to a couple of stories which

offer a lighter view of the artistic life of St Ives. “The Potter’s

Art” is the story of a young potter in St Ives who attracts the

attention of an older, wealthy patron. She has a history of taking

up various “painters, sculptors, writers, actors, and so forth. But

she had never had a real, live potter before”. She starts to hang

around his workshop, watching him shape his pots and noting that he

is physically attractive, as well as being talented. Eventually, she

spirits him away to

He is successful, though not happy about the lady’s personal demands

on his time and energies. And she is, he has begun to realise, older

than she looks. Needing an assistant for his work, “a young girl

student by the name of Miranda” is hired. She’s pretty and

enthusiastic about pottery, and the inevitable happens. They are

caught in “an unmistakably compromising position” and the girl is

ordered to leave. But the potter exacts his revenge on the older

woman in a bizarre way that gives a “twist in the tale” aspect to

the story. Some might say that the “twist” brings in the dark

element of the other stories. I was reminded of the sort of short

pieces that Gerald Kersh used to write when I read “The Potter’s

Art”. Like them, it doesn’t waste words and comes to a brisk

conclusion.

“Artists in Wonderland” explores a fairly well-worn idea, though in

an entertaining way. Dick Drake arrives in St Merry (an obvious St

Ives) after packing in his job as a bank clerk and determining to

become a painter. The only accommodation he can find in the by-then

popular art colony is in an old furniture van. He meets a young

woman who works as a model, and she helps him convert the van into

comfortable living quarters, and begins to educate him in the ways

of the art world. He can’t make any money with his paintings, so has

to hire himself out as a washer-up at various cafés. He attends a

local art school, where the teacher, Alice Sampson, takes him under

her wing after “learning that his uncle was the fabulously rich

owner of Drakes Ju-Jubes”,

a popular sweet.

Promoted by his teacher, and with the media enticed by the idea of

an artist living in a furniture van, Dick soon has an exhibition,

despite the fact that his paintings are only half-finished. He’s

also managed to establish a friendship of sorts with a famous artist

who lives in the area, and who appears to be more interested in his

collection of vintage cars than in offering Dick any useful advice

about painting. Boosted by the media, the presence of a

representative from the Arts Council, and the reluctance of anyone,

apart from his Uncle, to say that Dick’s paintings aren’t very good,

the exhibition seems to be a success. But Dick knows what the true

situation is, and when he’s offered a well-paid job with his Uncle’s

firm he, and the young woman he’d met earlier, immediately leave St

Merry.

Like I said, it’s a fairly familiar idea – the gullibility of the

art world – but it’s handled in an amusing way, and there’s no hint

of the darkness found in the other stories.

I can’t claim that Denys Val Baker was a major writer. He was

competent at producing novels and stories that largely skated easily

over the surface of the narrative and without delving too deeply

into the characters’ personalities or motives. Predictability might

have been a key factor in their overall effect, even when there was

an attempt to surprise. It’s mainly their relationship to the lives

of certain people, fictional and otherwise, from the St Ives

community that interests me. They may not stand comparison wIth Sven

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

A Journey with Love.

Crest Books,

The Face of Love.

Sabre Books, 1967. I have not seen this book, but it appears to be a

reprint of A Journey with

Love, though whether or not it uses the full text is not known.

As The River Flows.

Milton House Books, Aylesbury, 1974. This is a reprint of

A Journey with Love, but

with the first thirty or so pages omitted, and a short introductory

synopsis added. No acknowledgement is made to the earlier editions.

Company of Three.

Milton House Books, Aylesbury, 1974.

“A Work of Art” in A Work of

Art, William Kimber,

“Testament of a Green Eyed Man” in

The House by the Creek,

William Kimber,

“The Sacrifice” in Martin’s

Cottage, William Kimber,

“The Girl in the Photograph” in

The Girl in the Photograph,

William Kimber,

“The Potter’s Art” in The

Secret Place & Other Stories from Cornwall, William Kimber,

“Artists in Wonderland” in

The Girl in the Photograph, William Kimber,

There are several non-fiction books by Denys Val Baker which are of

relevance:

The Timeless Land: The Creative Spirit in

A View From Land’s End: Writers Against a Cornish Background,

William Kimber,

The Spirit of

Other books of interest:

The Cornish Review Anthology 1949-1952,

edited by Martin Val Baker, Westcliffe Books,

The Cornish World of Denys Val Baker,

by Tim Scott, Ex Libris Press, Bradford-on-Avon, 1994. Scott

contributed an article about Val Baker, with bibliography, to the

September, 1990, issue of

Book Collector.

Everyone Was Working: Writers and Artists in Post-War St Ives,

by Alison Oldham,

From a

“The Playground” in Why Do

You Live So Far Away?

by Norman Levine, Deneau Publishers, Ottowa, 1984.

The Dark Monarch

by Sven

I have only listed the books which directly relate to St Ives and

artists and writers. Val Baker wrote numerous other books (novels,

autobiographies, local histories, etc.) about

|