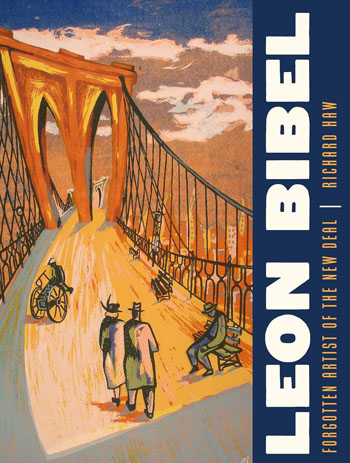

LEON BIBEL : FORGOTTEN ARTIST OF THE NEW DEAL

By

Richard Haw

Rutgers University Press. 300 pages. £41. ISBN 978-1-9788-2575-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

“Not many people have heard of Leon Bibel”, says Richard Haw in the

introduction to this fascinating book. He does go on to qualify his opening

statement by adding “even though thousands encounter him every day”, a

reference to the fact that Bibel was the model for the man at the front of a

bread line in the sculpture by George Segal at the Franklin Roosevelt

Memorial in Washington D.C.. Segal liked to use friends and neighbours as

models, but as he said, Bibel “was the only person I ever knew who stood in

a bread line”.

So,

who was Leon Bibel? He was born in 1913 in the Polish village of

Szczebrzeszyn, a part of which was the Jewish shtetl of Shebreshin. Bibel’s

father was a relatively liberal thinker and read Marx, Spinoza, and Kant,

whereas his mother was more religious. His father went to the United States

in 1920, and the rest of the family joined him in California, early in 1927.

Haw says that “San Francisco’s Jewish population was much smaller

than those in New York, Philadelphia, or even Los Angeles, but it was

vibrant, visible, and far less afflicted by the sort of prejudice found in

other parts of the United States….The residents of Jewish Fillmore were

nonconformist, primarily secular, and largely left-wing”. Commenting on

Bibel’s life in San Francisco, Haw tells us that he “went frequently to the

cinema in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and music halls and movie houses

would feature largely in his later art, as would the strong left-wing

politics he found on the streets and in the coffee-shops”.

Bibel was a student at Polytechnic High School and excelled at “fine art and

technical drawing”. He also “worked nights and weekends at Maria von

Ridelstein’s studio, where he took art lessons”. Ridelstein “was a former

Austrian baroness who had studied art in Rome, Paris, and Munich, and taught

in Japan and Chile”. She didn’t care for abstract art, and Haw is of the

opinion that she had an influence on Bibel’s early paintings. He says of

them that they are “plainly representational but are nevertheless open and

impressionistic in technique” Bibel later credited Ridelstein with

“developing his appreciation for ‘the use of colour and light’ “, as well as

introducing him to silk-screen printing. The 1932 oil on canvas “Self

Portrait with Violin” shows how Bibel effectively used colour to create an

eye-catching picture.

In

January 1933 Bibel enrolled at the California School of Fine Art (CSFA),

taking classes in Still Life, Elementary Drawing, and Life Drawing. He

“continued to help out at Ridelstein’s studio, as well as working part time

as a carpenter”. America was in the throes of the Depression in 1933, and

Bibel’s family had been badly affected as steady work dried up. Haw points

out that Ridelstein had no interest in politics and “The Depression played

no part in her art, even as its grip on the country and her city tightened.

Social realism - so prevalent in the conversations at the CSFA – was a step

too far for the Baroness, although it would eventually constitute the main

thrust of Leon’s art”.

Mural painting was popular in San Francisco, with the Mexican artist Diego

Rivera active in the city. Bernard Zakheim, described by Haw as “One of the

most political artists in San Francisco”, was also a presence to be reckoned

with. Haw additionally says that Zakheim was “stridently Yiddishist and

devoutly Communist, helping to create the Artists and Writers Union with

Kenneth Rexroth in 1933”. Bibel worked with Zakheim on murals for the Jewish

Community Centre and the University of California San Francisco Medical

School, illustrating how medical practices had changed over the centuries.

The illustrations in Haw’s book demonstrate how striking good murals can be

in terms of incorporating a wide range of personalities and activities.

Bibel’s decision to move to New York in 1935 was perhaps not surprising. He

was no doubt influenced by the idea that “all artists want only to go to New

York (You) don’t stand a chance anywhere else”, but also by President

Roosevelt’s creation of the “Works Progress AdminIstration (WPA), an arm of

which – The Federal Arts Project (FAP) – would pay artists to do exactly

what they were trained to do, which was make art”.

Bible clearly didn’t expect to get rich in New York, and Haw asserts

that “Artists like Leon saw themselves as ‘culture workers’ directly engaged

in the vital work of social change”, and he quotes him as saying, “They were

exciting times. Like artists everywhere, we were basically loners….but the

Artists Union and the Harlem Arts Centre…..were rallying points. We didn’t

have much money, but we had a good time. We would buy a bottle of sweet port

and sit up half the night talking”.

It

was during his New York years that Bibel’s work took on direct aspects of

what might be called political or protest art. I jotted down just a few

titles of his paintings, including “Idle Men”, “Posting of Jobs” (a hopeful

crowd gathered around a notice board), “The Lynching”, and “In the Shadow of

Liberty”, which has a large Statue of Liberty looming over a scene of a

mounted policeman swinging his baton to break up a crowd of demonstrators.

The latter item was a pen, brush and ink illustration, and the others oil on

canvas. I think it’s true enough to define Bibel’s style as largely

expressionist, as can be shown by another painting, “We Refuse to Starve”,

where a man carrying a placard bearing that slogan has fallen to the ground,

presumably due to having been attacked by the police. His face registers

what is likely a mixture of fear and pain, and his body seems distorted by

the fall.

At

this point it’s intriguing to ask why Bibel doesn’t appear in various books

dealing with radical American art of the interwar period? Bram Dijkstra’s

American Expressionism : Art and Social Change 1920-1950 (Harry N.

Abrams Inc., New York, 2003) might seem an obvious place to locate his work,

but you won’t find him there. Nor is he to be found in Helen Langa’s

Radical Art : Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (University of

California Press, Berkeley, 2004), though Bibel produced quite a few prints

in the Thirties. It’s understandable that he doesn’t rate a mention in

Andrew Hemingway’s Artists on the Left: American Artists and the

Communist Movement, 1926-1956 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002).

Bibel doesn’t seem to have ever had links to the Communist Party, or if he

did Haw doesn’t mention them. He did produce a portrait of Lenin in full

flight as an orator, and one of his paintings, the 1938 oil on canvas

“Subway Scene”, did include a copy of the Communist New Masses,

which might be taken as indications of his political sympathies. There was

also a mural he painted for The Followers of the Trail, “part of a cluster

of Jewish working-class camps that sprung up in the Hudson Valley….The camp

became a favourite destination for New York Jews, primarily from the needle

and fur trades. Members were primarily Yiddish speaking, working class

communists”. Bibel’s mural included portraits of Marx and Lenin.

Finally, there is Francis Booth’s Comrades in Art : Revolutionary Art in

America, 1926-1938, a useful but curious book, published in 2012 but

with no other details showing. It lists numerous left-wing artists, but not

Bibel. I’ve just looked at a few publications I have, and there may be

others that do refer to Bibel, but I doubt it. When the books I’ve mentioned

were published he was almost a forgotten man.

One

of the reasons for Bibel’s seeming later neglect as an artist may have been

that he was employed by the Arts Teaching Division of the FAP and taught at

a school in the Bronx, and at Bronx House, a settlement house founded in

1911. I suspect that, not having worked on any major murals or other

significant projects, his teaching job in the Bronx led to his being

overlooked when art historians came to compile records of artists employed

by the FAP. Add to this some other developments in Bibel’s life, which will

be made clear later, and his neglect becomes more understandable.

The

teaching commitments did not stop Bibel from continuing to create works

commenting on contemporary events. The oil on canvas “Escape over the

Pyrenees”, showing refugees burdened with whatever possessions they could

carry, was an obvious reference to the Spanish Civil War. The stark

lithograph, “Fear from Above”, could have the same relevance, aerial

bombardments affecting civilians being a significant factor in Spain. A

brush and ink “Machine Cogs” shows rows of workers almost as extensions of

the machines they’re operating, and a pen and ink sketch, “Hopeless”,

focuses on a man with his head bowed in defeat and is a comment on

unemployment and poverty. Haw at some point refers to Tom Kromer’s

Waiting for Nothing, surely one of the darkest of Depression novels, and

a quote from it can easily apply to Bibel’s sketch : “These are dead men.

They are ghosts that walk the streets by day”.

One of the more striking oil on

canvas creations from 1938 is “Home Relief Office”, where what looks like a

reasonably well-groomed man observes rows of others patiently waiting to be

seen by the staff. That it appears to portray a more white-collar air of

want put me in mind of one of the memorable poems of the Depression years,

Alfred Hayes’ “In a Coffee Pot” (“You’ll find us there before the office

opens/Crowding the vestibule before the day begins”).

I

don’t want to give the impression that Bibel’s art works were solely focused

on social and political themes. Haw provides a variety of examples to

illustrate Bibel’s range of interests and involvements. The well-arranged

“Eugene Smoking” (an oil on canvas portrait of his friend, Eugene Etler),

the lithograph of his wife, Neysa, several silkscreens, “Sunflowers”,

“Abstract Boats”, “Net Menders, “Cape Cod Village”, “Red Hot Franks” and the

powerful (to my eyes) oil on canvas, “Window Cleaner”, point to an artist

alert to and engaged with everything around him. It might be worth noting

that a print of “Red Hot Franks” is held in the British Museum collection of

American prints, and is one of the illustrations in Stephen Coppel’s The

American Scene : Prints from Hopper to Pollock (British Museum

Press, 2008).

Haw

notes that “Slowly during the mid-1930s, conservative Democrats, along with

their Republican allies, began to mobilise against the New Deal”. When, in

1938, the economy started to show signs of another slow-down, and the WPA

took on more unemployed workers, the conservatives launched an attack on

Roosevelt’s policies. One of the main targets was the WPA’s cultural

programme, with accusations that an organisation like the Federal Theatre

Project was using public money to spread communist-influenced ideas. But

there were other reasons for the reaction against the New Deal. Haw quotes

Harry Hopkins as suggesting that America was “bored with the poor, the

unemployed and the insecure”. But he’s also of the opinion that, as

prosperity increased, “many rediscovered their faith in individualism, in

the process giving up on large government programmes”. The result was, in

Bibel’s case, that he was fired from his teaching job when funds dried up.

His

wife did have some work as a supply teacher, but her earnings, with what

little Bibel got from any sales of his artworks, were not sufficient to

survive on in New York. Together with her parents, a decision was made to

move to New Jersey in 1942 and become chicken farmers. As Haw puts it: “Leon

and Neysa’s move to New Jersey was inspired and somewhat desperate, and it

completely changed their lives. They were artists and teachers, concertgoers

and dancers. They had been ’city people’ and now they were farmers, thrust

upon the land, or at least upon the fortunes of a small band of fowls”. The

changes in their lives that this brought meant that Bibel effectively gave

up any creative work for the next eighteen years.

He

started to paint again in the early 1960s, partly due to the friendship and

encouragement of the sculptor, George Segal, who by that time had

begun to establish a reputation on the American pop art scene with “cast

life size figures and the tableaux the figures inhabited”. Segal, a one-time

chicken farmer himself, had originally been a painter and gave Bibel a stock

of unused canvases to work on. It’s significant that Bibel did not return to

the representational and socially-committed paintings he had produced in the

1930s. Those times, with their social and political problems, had passed. As

he remarked about his New York years, he “was deeply involved in the world

situation, but when I went back to painting after 18 years I was no longer

involved….I was uncomfortable with the old subject matter, (I) didn’t feel

it philosophically”. Instead, he

began to experiment with geometric abstract compositions. There are several

examples in the book, and one, the oil on canvas, “Untitled (Colour)”, is

interesting to look at, though a couple of others, “Sunset” and “Apple

Tree”, come across to me as little more than decoration. But I admit to not

being an enthusiast for geometric abstraction. And I would be less than

honest if I didn’t say that Bibel’s work, as it related to the art and

politics of the 1930s, is where my interest in him is to be found. I can

respect an artist’s right to choose what to do, and to change the style and

focus of his work, but that doesn’t mean I have to like what he does. I

doubt that it would have bothered him. Haw says, “He made the art he wanted

to make and that was that. Whether anyone liked it or not seemed beside the

point”. Bibel insisted, “Selling is not my prime reason for doing

anything…..Everything is commercial. Everything is fluff. But I don’t have

to do anything. I do what I like…..I have enough to eat”.

Leon Bibel died in 1995. He is to be admired for having survived the years

of the Depression while creating some worthwhile art, then finding a

practical way to support his family, and finally returning to painting and

related activities. Richard Haw has done him justice by producing an

informative and richly illustrated book that tells his story.