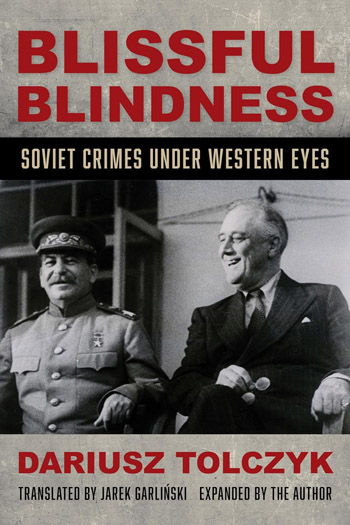

BLISSFUL BLINDNESS : SOVIET

CRIMES UNDER WESTERN EYES

By Dariusz Tolczyk

Indiana University Press. 427 pages. £45. ISBN 978-0-253-06709-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

“Soviet propaganda proved impressively effective in its efforts to deceive,

corrupt, pressure, and manipulate many Western opinion makers”. So says

Dariusz Tolczyk near the beginning of his impressively detailed account of

how and why so many people seemingly closed their eyes to what was happening

in Russia once the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917.

There was a brief period when it may have been understandable that

hopes for a better future inspired people to believe that everything was

possible, and that some sort of, if not perfect, more-equable society could

be established and provide a guide to a wider distribution of the world’s

wealth. In the 1920s such dreams did not appear unreasonable to many outside

Russia and the propaganda makers in that country realised this and worked to

construct an image, or series of images, that would cater for the needs of

the dreamers.

It wasn’t as if the dreamers came from disadvantaged parts of the social

structure where opportunities for education, travel and other factors, that

might have led to greater awareness of the way the world functioned, were

restricted. Any number of “Western

intellectuals, writers, artists, journalists, clergymen, businessmen, and

politicians” flocked to visit Russia and came back convinced, or so they

said, that they had seen the future and it worked. What they had actually

seen in most cases were cleverly orchestrated performances staged for their

benefit and having little or no relationship to the realities of life in

what had quickly become a dictatorship, not of the proletariat but of the

privileged members of the Communist Party, and even within that party of a

minority of opportunistic activists who had little regard for the safety and

concerns of the mass of the population. They could justify any measure, no

matter how extreme, by saying it was in the interests of the Revolution :

“Violence was the reflexive response of the new revolutionary regime to the

basic problems of the country it now ruled”.

Tolczyk says that there was a “fascination with Bolshevik violence that

gripped many writers, artists, and intellectuals”, including some of those

from other countries. They could easily make up excuses for the operations

of the NKVD if they became aware of them. And if we accept Tolczyk’s

definition of intellectuals – “people more inclined than others to see the

world in terms of, ideas, abstractions, and generalisations” – the effect of

violence on individuals was lessened in their thinking. Provided it didn’t

happen to them.

Among the early admirers of the Russian Revolution was the American

journalist John Reed who wrote what is often seen as a “classic” account of

the Revolution in Ten Days That Shook

the World. Some might argue that

there’s an indication of a still-lingering admiration for revolution in the

fact that Reed’s exploits inspired

Reds, a Hollywood epic. Tolczyk writes of

“ the scribbling class’s fascination with men of action”,

a description which might also apply to filmmakers. Reed, a romantic

revolutionary if ever there was one, must have known what was going on in

Russia, and there have been suggestions that he might have

been on the brink of becoming disillusioned with how the country was

developing. But he died young and was turned into something of a hero, an

American who gave his life for the Revolution. Did the Bolsheviks cynically

use him in both life and death to further their cause and persuade more

foreigners to support it?

There were plenty of foreigners who willingly went to Russia, or at least to

the parts of it they were allowed to visit. Some were members of the working

class attracted by the promise of work or because they believed that a new

society was being constructed on their behalf. It’s doubtful that too much

attention was paid to them, and the records seem to show that, if it was

possible, some returned to their native countries. Others, however, stayed

and eventually “disappeared” into labour camps as paranoia about plots to

overthrow the Bolsheviks mounted and all foreigners became automatically

suspect. Tolczyk lists Fred Beal’s

Proletarian Journey (published as

Word From Nowhere in Britain)

in his

bibliography. Beal was a union organiser and member of the American

Communist Party and, during a strike in Gastonia, North Carolina, an attempt

was made to frame him on a murder charge. He fled to the Soviet Union, but

eventually returned to America and the prospect of a prison sentence rather

than stay in a Russia he had become disillusioned with during his employment

at the Kharkov Tractor Plant.

Others (what Malcolm Muggeridge referred to as “the progressive

elite.....academics and writers...the clerks of Julian Benda’s

La Trahison des clercs”),

however, with more to offer in terms of their potential for influencing

public opinion abroad, were often given priority treatment and taken on

carefully arranged tours of showcase factories, farms, prisons, and other

establishments. In return they seemed happy to sing the praises of Stalin’s

new society. And of the man himself. H.G. Wells, after meeting the Soviet

leader, said “I have never met a man so candid, fair, and

honest.....Everyone trusts him”.

And what are we to make of Harold Laski, “a famed British political

scientist”, who wrote glowingly of Russian prisons where the inmates had “a

good supply of newspapers, periodicals and books.......wireless, classes in

cultural and vocational subjects”, and “a prison newspaper, in which the

right to make complaints is an essential feature”.

The “eminent British jurist and

Labour Party politician D.N. Pritt” visited the Gulag in 1932 and was so

impressed with what he saw that he said, “a substantial part of the

population ....nevertheless prefer to continue living in the prison”. The

American radical writer Anna Louise Strong was of the opinion that “So well

known and effective is the Soviet method of remaking human beings that

criminals occasionally now apply to be admitted (to the Gulag)”.

Perhaps one of the more extreme examples of someone who, for one reason or

another, consistently presented a positive view of the Russian experiment

was the journalist Walter Duranty, the Moscow corespondent of the

New York Times. In his case it

can’t be argued that he was “tricked” into seeing only what the Soviets

wanted him to see. He had “managed to ingratiate himself with the Bolshevik

authorities” who he presented in his reports as “a group of sensible

liberals and progressives”. Alleged Soviet atrocities were, he claimed, “to

a great extent the product of Western propaganda”. “He denied the rumour of

mass starvation in 1921”, and “In

the 1930s he denied the existence of the famine, terror, executions, mass

deportations, and slave labour”.

Duranty’s reporting was well-received

in the United States,where he “enjoyed great prestige in the American

cultural, political, and economic establishment as a leading expert on

Soviet affairs”. Tolczyk says that he was instrumental in persuading

President Franklin D. Roosevelt to grant “official recognition to the USSR”.

American exports were a way of alleviating some of the effects of the Great

Depression, and business interests were keen to expand them into Russia, so

glowing reports about conditions there were welcomed. No-one wanted to hear

other views. When Gareth Jones wrote about his experiences in Russia in the

early-1930s, and the famine and other problems he observed, he was attacked

by Duranty and other journalists, and was refused permission to visit Russia

again.

The war years, at least after June 1941 when Germany invaded Russia, saw

another period of pro-Soviet propaganda. Prior to that the 1939 Nazi-Soviet

Non-Aggression Pact had raised doubts in the minds of some communists and

fellow-travellers. But it was explained away as Stalin’s plan to delay the

inevitable war with Germany and give him time to build up the Russian armed

forces. Once the war did start, and Russia became allies with Britain and

America, communism became almost respectable, criticisms of conditions in

Russia were forgotten, or at least conveniently overlooked, and

a process of placing Stalin on a par

with Churchill and Roosevelt got under way. Churchill never was taken in by

Stalin but knew he was needed as an ally until Germany was defeated, whereas

Roosevelt does appear to have thought of him as someone who could be

reasoned with “and will work for a world of democracy and peace”.

It’s a personal anecdote but I recall going to the local cinema in the

northern industral town I grew up in during the war years and, after the

National Anthem had been played, hearing “The Cossack Patrol”, as it was

known (Glenn Miller’s wartime orchestra recorded it as “Meadowlands”),

coming over the loudspeakers as we filed out. And the “Second Front Now”

slogan scrawled on a nearby wall. Both were examples of how Russia was

thought of favourably at that time. Hollywood films also saw the Soviets in

a sympathetic way. Tolczyk lists a few of them

- Song of Russia and

North Star, with the well-fed workers determined to drive the Nazi

aggressors from their land. In

Mission to Moscow, based on a book by Joseph E.Davies, one-time

Ambassador to Russia, a smiling and friendly “Uncle Joe” smokes his pipe and

looks thoughtful. The show trials of the 1930s are shown with Bukharin,

Yagoda and Radek freely confessing to their “crimes”, including associating

with Trotsky. The screenwriter, Howard Koch, presumably believed, like

Davies, that all three of the accused were guilty. Or did he? He rather

glossed over this episode in his autobiography,

As Time Goes By: Memoirs of a Writer,

implying that writing the

screenplay was a job imposed on him by the studio and taken on by him

reluctantly.

There were still apologists for Russia into the 1950s, despite the takeover

by Stalin of countries like Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and others

behind what became known as “The Iron Curtain”.

But the onset of the Cold War and events like the Berlin Airlift, the

Korean War, the Kruschev revelations of Stalin’s crimes, and the Russian

suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, had combined to reduce

support for communism in the West. In addition, more and more accounts of

life in the Gulag had appeared and it was difficult to refute them in the

way that had been done in the 1930s when lone voices could be ignored or, if

necessary, attacked as those of bitter dissidents, capitalist troublemakers,

and Trotskyists. The story of George Orwell’s

difficulties when trying to have his

Homage to Catalonia published on

his return from the Spanish Civil War is well-known, but he wasn’t alone in

having to deal with publishers and editors reluctant to have anything

negative said about the Soviet Union. By the 1950s publishers were looking

for material that gave the lowdown on what had happened under communism in

Russia and elsewhere.

I’ve moved through Blissful Blindness

aware of the fact that it’s so packed with information that it would have

been impossible for me to refer to it all in a review. Tolczyk incorporates

personal accounts by survivors into his narrative, with some of them

extremely disturbing in their details of methods used by interrogators to

obtain confessions. He also gives some statistics relating to the number of

people killed by the NKVD and similar organisations. Again, the details are

harrowing. The Katyn massacre of Polish officers has been written about

elsewhere but can still horrify. Writing about the period in 1937-1938 known

as the Great Terror, Tolczyk says that “the NKVD arrested 1,575,000 people

and executed 681,692 of them – according to official records. Estimates of

the real number tend to be higher, around 750,000”.

It’s probably impossible to

determine how many of these people were not guilty of any kind of crime and

were simply rounded up so quotas could be met. But I would guess that the

madness of the time meant that most of them were completely innocent.

One more personal anecdote. When I was a young soldier in the British Army

in Germany in the early-1950s I had a girlfriend who told me that, as a

child, she remembered taking water out to some soldiers who were resting in

her family’s orchard. They weren’t Germans, probably Ukrainians who had been

fighting with the Germans, and were clearly terrified when they thought the

Russians were getting closer. I was reminded of this when I read the account

in Tolczyk about what happened to the Cossacks serving with the German army

who surrendered to the British on the understanding and with a guarantee

that they wouldn’t be handed over to the Russians. But orders came from

higher up the command chain to the effect that there was an agreement with

Stalin to do just that, so British and American troops were ordered to force

the Cossacks into Russian custody. “Force” was the operative word, and it

led to suicides and other acts of despair among the Cossacks and the

families they had with them: “Witnesses -

both escapees and British soldiers – recall mothers jumping into the

river holding children in their arms........the soldiers found hanging from

the trees the bodies of Cossacks who preferred to die rather than return to

their homeland.” One British officer saw a Cossack shoot his wife and three

children and then himself. It was a

shameful and tragic episode.

Blissful Blindness

is a book that deserves to be read by anyone who still harbours illusions

about what Soviet communism stood for and what it became. Written clearly

and without recourse to unnecessary theorising, it has extensive notes and a

good bibliography.