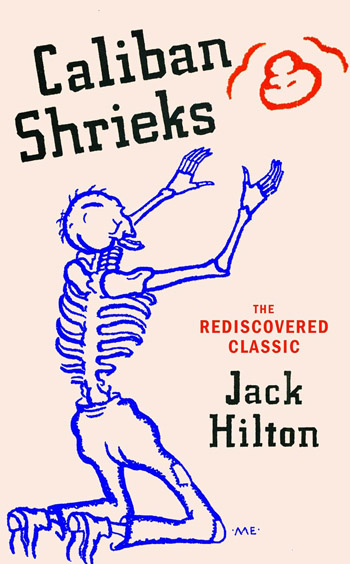

CALIBAN SHRIEKS

By Jack Hilton

Vintage Classics. 162 pages. £16.99. ISBN

978-1-784-87875-7

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Who was Jack Hilton and why, almost ninety years after his book was first

published, has it now been republished? He was born in 1900 in Oldham into a

working-class family and at an early age was employed in a cotton-mill as a

half-timer. A half-timer was a boy or girl who went to school on a part-time

basis and to the mill in the same way. I sometimes wonder if my father, born

in 1895, had a similar experience ? Hilton didn’t last too long in the mill,

though long enough to remember its “hellish noise, wheels going round,

motions, speed”. My mother worked in those conditions for years. My own

brief encounter with a cotton mill persuaded me that I didn’t want to spend

too much time there and I joined the army.

Hilton also enlisted, though in different circumstances to my own. He was

seventeen, lied about his age, and was shipped over to France and saw action

against the Germans, during which he was wounded. Interestingly, some of the

routines and types he describes when writing about life in army camps in

Britain reminded me of my own experiences, though they came almost forty

years after his. The regimentation hadn’t changed a great deal. Luckily,

though, I never needed to fire a rifle in anger during my three years in

uniform, nor did I have to face up to a scramble for work when I left the

army.

“Back we came,” says Hilton, “dribbling home in penny numbers. Hometownism,

twenty-nine shillings on the dole”. It wasn’t the “land fit for heroes” the

politicians had talked about, and Hilton noticed the “fat, stay-at-home tin

gods” who knew how to preserve their positions. On his return Hilton got a

job as a plasterer, and joined the union representing that trade. He soon

began to take an interest in wider issues : “politics were to be the school

whereby I grew a little out of my ignorance”. One thing he realised after

listening to politicians of various persuasions was that the “drum of

Parliament’s purpose was to

give promises to all”.

A period “on the tramp” gave Hilton insights into human behaviour. One of

his observations was “How the blinking police had you taped. The cold,

professional, steely stare. I remember going to one police station for a

putting-up for the night; but they know the law. There is a ‘spike’ seven

miles away, and you are told to ‘beat it quick’. Any remonstrance is met

with an unceremonious thrust into the middle of the roadway”.

He adds that he “found the milk of human kindness improved the more

rural I got in location. The John Hodge with his cot and kids seemed

incapable of refusing to give a buttered slop-stone to one in need. The

hospitality of the village pub was generous. A song and a couple of standard

overtures like ‘Zampa’ or ‘William Tell’, finished off with a recital of

‘Liberty’ by Lord Lytton. This is what they like and you are right for a

pint and a copper collection”.

Better that than the ‘spike’ or other forms of accommodation for

down-and-outs. Hilton outlines some, such as Salvation Army hostels, with

their general characteristics of “cleanliness” and “institutionalism”,

though he didn’t like to stay in them because of the “gallant lasses” who

visited to sing hymns. He thought their “Christian virginity” dispiriting.

But there were also places where you had to break stones to earn your

keep, and others where for half the price of a bed you could have a

“sit-up”. You slept in a chair,

though I somehow doubt it was a comfortable armchair.

When he became active in politics he associated with what seems to have been

a small group not noticeably aligned to any particular party or

policy. Hilton and his fellow-activists campaigned on behalf of the

unemployed, and there is some evidence to suggest that he worked with Wal

Hannington in the National Unemployed Workers Movement (NUWM). He was

arrested for leading a demonstration in Oldham, spent time in Strangeways

prison in Manchester, and when released was bound over to keep the peace by

not addressing any meetings for three years.

He does admit that “Of course we were guilty: vile language was

used, windows were broken, stones were thrown, assaults were committed. A

mob was unleashed : it was angry, it was hungry, it was underfed”.

Hilton’s account of prison life is bleak : “Little need now for flogging,

dungeons and foulness. You can do it with clean air and light. Just make

everything the same – so silent – so solitary – so inhumanly civilised.

Slowly comes your turn to go up to a

table on which lie bundles of books”. The books? “Holy Bible, a book of

texts and a Christian sermon in story form about sinners at the crossways”.

This was a time of inspirational

tracts. Somewhere, Hilton mentions

Her Benny by Methodist preacher Silas Hocking, though it dates back much

earlier than the interwar years. It was still around when I was growing up

in the 1940s and I recall reading it.

Hilton’s view of many of the people he met in prison was that they were

“only the petty criminals of society, mostly created out of a position of

poverty, and inability to capture life’s loaf in the sweet pacific way of

honest toil”. And he adds : “The Bishop, the Banker, the large-scale

Landlord, the Company Director, and the business man, need break no law of

parliament’s making in order to get their temporary needs met”.

I couldn’t help thinking of my father taking me for a walk one Sunday

morning. We passed the local prison and when I said something about the

people inside, he replied, “The biggest thieves aren’t behind bars”. He

wasn’t a particularly political man, but from occasional things he said I

got the feeling of the pre-1914 world, and the days of popular revolt and

syndicalism. An old rhyme from

those days comes to mind : “This is a free country/Free without a doubt/ If

you haven’t got a dinner/You’re free to go without”. It might even be

applicable now to some people.

There is a long chapter in Caliban

Shrieks in which Hilton discusses the various political parties offering

panaceas for the problems of unemployment, low wages, and such matters. He’s

dismissive of “book socialists” whose “ferocity is confined to the iron

rigidity of terminology.....If you asked them the reason R.I.P. is placed on

gravestones, they would say it was to commemorate capitalist Rent, Interest

and Profit”. He goes on to castigate the Independent Labour Party, and the

Labour Party, which yearns for respectability and acceptance (“any turncoat

from other camps is welcomed”; it rings true now as well as then). And the

Communist Party, which didn’t mind being outlawed by other socialist groups;

“They could get on with the job unfettered. Slandering all and sundry was

made acceptable to their poverty-stricken listeners by their dogmatic

assertion that they, the working class, are the cream of the milk jug”.

He doesn’t leave out the trade unions. He saw them as “in the groove of

conciliation, adjustments and inertia”. To be fair, he does acknowledge the

fact that union membership had shrunk by about a third as the Depression

deepened, so they had less power. But

he is contemptuous of union officials

: “There are quite a lot of organisers in the many trade unions. It

is an escape from poverty and hard work, a rung in the ladder to becoming an

executive member or even to the General Secretaryship”.

Hilton never says what his own

political affiliations are, if he had any, but his basic attitudes appear to

me somewhat similar to those of rank-and-file members of the Industrial

Workers of the World, the famed Wobblies, whose heyday was from 1905 to

around 1925.

What happened to Hilton after Caliban

Shrieks was published in 1935?

There doesn’t seem to be a great amount of detailed information about

his life, particularly his later years, easily avaIlable. There are a couple

of otherwise useful and interesting pieces accompanying Hilton’s text, but

they mostly focus on how his book was rediscovered. He attended WEA classes,

was at Ruskin College for a time and we know he published four other books,

including two novels, the last in 1950. He then stopped writing and returned

to his old trade as a plasterer. He died in Oldham in 1983.

Is Caliban Shrieks a “lost

classic”? I’m always wary of terms like “classic” and “genius”. They’re

probably useful as marketing ploys, but may not amount to much beyond that.

But Hilton’s book is quite remarkable and not just because it is a record of

another time and another place. Had it been simply that and written in an

acceptably functional manner I doubt it would have been republished. It is

the quality of the writing which has given it the capacity to survive.

It would be valuable to know which writers Hilton had read beyond one or two

he mentions. Shakespeare is significant, but few, if any, of Hilton’s

contemporaries are there, though we are told he was friendly with George

Orwell and the North-East writer, Jack Common.

He had a style which was rich with

colourful expressions of the formal and informal kind, with both skilfully

incorporated into the wider text. Sometimes the statements almost sing : “Oh

London of Dick Whittington, you are infested with people of poverty, your

crypts under St Martin’s in the Fields, your night shelters, your Starvation

Army”. It is not conventional proletarian prose of the 1930s variety, nor

does it express what are thought of as conventional proletarian ideas. His

workers and the unemployed are rarely revolutionary in intent, just tired

and hungry.

Jack Chadwick, who was largely responsible for locating an old copy of

Caliban Shrieks and getting it

back into print deserves our gratitude for doing so. It was something I knew

about, thanks to Andy Croft’s fine survey of British fiction of the 1930s,

Red Letter Days, but never

expected to be able to read.

.