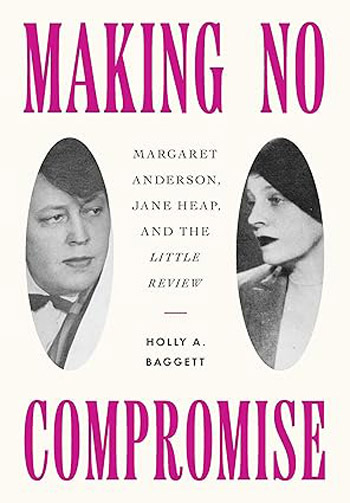

MAKING NO COMPROMISE : MARGARET ANDERSON, JANE HEAP, AND THE LITTLE

REVIEW

By Holly A. Baggett

Northern Illinois University Press. 296 pages. £28.99. ISBN 978-1501-771446

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Little magazines were essential to the development of the modernist movement

in literature. Without them it may have been difficult for struggling

writers to find outlets for the new, the experimental, and anything that

stood outside the framework of established and accepted forms of novels,

short stories, and poems. And even if many little magazines didn’t aim to

deliberately break new ground they often drew attention to young writers and

to others who had been overlooked or unfairly forgotten.

The Little Review was founded in Chicago in 1914 by Margaret

Anderson, a lady escaping from her dull roots in Indianapolis. Chicago, at

that time, had a lively bohemian literary and political community. Writers

like Floyd Dell. Ben Hecht, and Maxwell Bodenheim were active. Holly Baggett

points out that Bodenheim’s early novel, Blackguard, originally

published in 1923 and recently reprinted, “was a thinly veiled account of

the literary scene during the Chicago Renaissance”, with Anderson appearing

under the name Martha Apperson.

Also active in Chicago was the anarchist Emma Goldman, with her magazine,

Mother Earth. And Harriet Monroe with Poetry. In addition, the

IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) had its headquarters there, and was

busy promoting the idea of syndicalism and direct action to further its

policies. Its publications often used poems to hammer home its message.

The first two years of the Little Review were heavily shaped by

Anderson’s interests. Baggett describes the magazine as a “personal

enterprise” and says it “repeatedly referenced mid-to late Victorian

dissidents such as Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde alongside their Edwardian

successors Galsworthy and Wells while engaging in the modern Imagist poetry

wars of the early twentieth century”. Anderson’s friendship with Emma

Goldman was also in evidence when articles about anarchism and Max Stirner

appeared in the Little Review. Stirner’s The Ego and his Own

was “a widely read piece of work in anarchist circles” and Baggett is

certain that Anderson was familiar with it. It exercised a great influence

on individualist anarchists and members of the artistic community.

The contents of the Little Review began to change from around 1916

when Anderson met Jane Heap. She came from Kansas and had studied at the

Chicago Art Institute where she was commended for “outstanding work in

figure drawing and composition”. She then moved to Germany where she learned

“tapestry, weaving, and mural decoration while living in an artist’s colony

near Munich”. When she returned to Chicago she taught at “Lewis institute

where she had at one time studied jewelry making and participated in

theatrical productions”. Like Anderson she was a lesbian, though unlike her

she was more outgoing about her feelings. Male bohemians and their

contemporaries often commented on Anderson’s attractive figure, femininity

(she always dressed well) and good looks, whereas Heap indulged in

cross-dressing and left no-one in any doubt about her sexual preferences.

Both women shared an interest in the ideas of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff,

which, says Baggett, drew them into “the world of mysticism”. Opinions about

him seem to have varied. Was his “esoteric philosophy” genuine or a mixture

designed to distract from any serious consideration of it? Baggett points to

the fact that “To some observers, Gurdjieff was little more than a

self-serving obnoxious fraud who bamboozled Anderson and Heap along with

other members of the literati”. She

devotes a whole chapter to his influence on the two women and, through them,

the contents of the Little Review. I haven’t the space to weigh the

pros and cons of his appeal, but there’s no doubt about the fact that many

well-educated, intelligent people fell under his spell, perhaps because they

were searching for something which might replace the faith they had lost in

a world that was increasingly complicated and violent. According to Baggett,

among those who were followers of Gurdjieff’s teachings, and had work

published in the Little Review, were Muriel Draper, Hart Crane,

Gorham Munson, and Jean Toomer. Not all of their names will be recognised by

contemporary readers, but they were known in their day.

Ezra Pound was drawn into the world of the Little Review when he took

on the role of European editor. It was through him that W.B. Yeats, James

Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Wyndham Lewis began to appear in the magazine. The

relationship to the occult or aspects of Eastern philosophy is relevant

here. Baggett notes that Pound had an “interest in Eastern literature and

philosophy” and asserts that “several scholars now endorse the notion that

while he publicly rejected the occult, he was nevertheless fascinated, if

not obsessed, by it”. She adds that Yeats’s “history with the occult is well

documented”, and quotes another scholar, Stuart Gilbert, to the effect that

“it is impossible to grasp the meaning of James Joyce’s Ulysses and

the significance of its leitmotifs without an understanding of the esoteric

theories which underlie the work”.

It wasn’t the esoteric that landed Anderson and Heap in court when they

started to use excerpts from Ulysses in the Little Review in

1920. The charge was the more down-to-earth one of “circulating obscenity

through the mail”. It could be that it was the Ulysses trial that

gave the magazine a notoriety that ensured its place in the history of

literary modernism. Baggett outlines the story, and the judgement which

found the editors guilty and fined them, a fact which may have had an effect

on the magazine’s future. It continued to appear, though there was a slowing

down in its regularity. Only five issues came out between 1925 and 1929.

Money was always a problem for little magazines, especially those attempting

to publish anything new or different.

There is a chapter in Making No Compromise which focuses on “Lesbian

Literature, Women Writers, and Modernist Mysticism” and offers some useful

information and insights into Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, Getrude Stein, Dorothy

Richardson, May Sinclair, Mary Butts, and the “first American Dada”, the

strange Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. I have to admit that I’ve

never known how seriously to take the latter eccentric who, in earlier

accounts I’ve read, was noted more for her odd behaviour than any literary

talent. More recent considerations, especially those by historians of

modernism, have thrown new light on her writings. She now occupies a place

in an anthology like Modernist Women Poets, edited by Robert Hass and

Paul Ebenkamp (Counterpoint Press, 2015) where her work sits easily

alongside that by Mina Loy, Getrude Stein, Lola Ridge, Amy Lowell, and

others. There is a valid point made by Baggett when she says that “modernism

itself can be re-evaluated through the prism of feminist literary

perspectives”, though the anthology shows that men can also be active in

that field.

I was interested in what Baggett had to say about Mary Butts, a writer I

began to be fascinated by when I found, on a side-street book stall in

Liverpool, a copy of Speed the Plough, a collection of her short

stories published in 1923. Baggett refers to her “distinctly bohemian life

in London and Paris in the circles of Pound, Sinclair, Stein and Cocteau. In

the twenties, Butts began a lifelong habit of using opium, hashish, and

heroin”. She also made “fervent explorations” into the occult, which took

her into the dark world of Aleister Crowley, and his “infamous” Abbey of

Thelema in Sicily. Pound,

Virginia Woolf, Ford Madox Ford, and others praised her work, but Sylvia

Beach described her life as “tragic” and she died in 1937 when she was 46.

Years ago I found a copy of The Best Short Stories of 1924 in a

second-hand bookshop and read her story, “Deosil”, reprinted from The

Transatlantic Review. Along the way I picked up other items relating to

Butts, including a copy of Little Ceasar 12 from 1981 which had a

short tribute to her by Oswell Blakeston who had known her in the 1930s. The

full story of the adventures and experiences of Mary Butts can be found in

Nathalie Blondel’s 1998 biography, Mary Butts : Scenes from the Life.

As the Little Review moved into the 1920s it was obvious that Jane

Heap was the dominant influence on what it published. She had little or no

interest in the kind of “missionary zeal” that Baggett says both Anderson

and Pound shared when it came to presenting new work to the public. She

quotes Heap as writing that it was “of no interest” to her whether the

American public came to appreciate art “early or late or never”. It’s an

attitude I’ve sometimes heard expressed by little magazine editors and

writers over the years, and it denotes a kind of “purity”, but it is hardly

likely to increase the circulation of a publication which is probably

struggling to stay alive, anyway. As I mentioned earlier, only five issues

of the Little Review appeared between 1925 and 1929.

Very few little magazines have survived for more than a handful of issues,

but the Little Review managed to stay alive from 1914 to 1929 by, in

Baggett’s words, “bringing attention to every major movement in early

twentieth-century literature and art”. And

she adds, “In the twenties Heap issued numbers that included every movement

from Cubism, surrealism, Russian Constructivism, and De Stijl architecture

to Bauhaus, modern theatre design, and Machine Age aesthetics”. A long list

of the names of those featured in the magazine includes Man Ray, Max Ernst,

Hans Arp, Joseph Stella, and George Grosz. I have a copy of the Winter 1924

issue which spotlights Juan Gris alongside Hemingway, Stein, Paul Eluard,

Francis Picabia, Dorothy Richardson, Nathan Asch, and others. I’m also

inclined to point to The Little Review Anthology, edited by Margaret

Anderson in 1953, and which provides a good impression of the range of

contributors and their concerns.

I think it’s worth quoting what Jane Heap said when “defending her right to

publish what she pleased”: “We have printed more isms than any other ten

journals and have never caught one. Our pages are open to isms, ists,

ites…we have been after the work, not the name….our drooling critics, in

true American fashion, become sea-sick over a name…we are enjoying

ourselves”. I like that

phrase, “we have been after the work, not the name”, which seems to me to

sum up an ideal policy for a little magazine, printing something because

it’s interesting and not because it fits to a preconceived notion of what a

work of art should be.

Making No Compromise

is a book packed with information about a significant publication and the

personalities behind it, and is sure to appeal to anyone interested in

literary modernism, women writers, and little magazines. I’m conscious of

perhaps not indicating how much it covers in terms of the people it

published and their ideas. Holly Baggett is rightly keen to show how women

editors and writers were involved in what came to be known as the modernist

movement, and the value of their contributions to it. She also indicates how

a magazine like the Little Review played a prominent part in bringing

writers together in ways that could allow them to develop their own ideas

but also see what others were doing. And open up their work to the attention

of a discerning audience.

There are photos of some of the principal actors in the Little Review

story, useful notes, and an extensive bibliography. Having enjoyed the book

so much It possibly seems churlish to pick up on one thing that bothered me.

However, on page 26 Baggett says that Margaret Anderson, while raising funds

for her magazine in 1914, went to New York to “get advertising revenue from

major publishers…. While at Scribner’s she met a young F. Scott Fitzgerald

who was going over the proofs for his first novel, This Side of Paradise”.

Fitzgerald’s novel was only published in 1920, so Anderson couldn’t have met

him at Scribner’s in 1914, despite what she says in her autobiography, My

Thirty Years War, published in 1930, which is where Baggett drew her

information from. I have a copy of Anderson’s book and it’s quite clear

she’s mistaken when she recalls meeting Fitzgerald correcting proofs of his

novel around 1914.