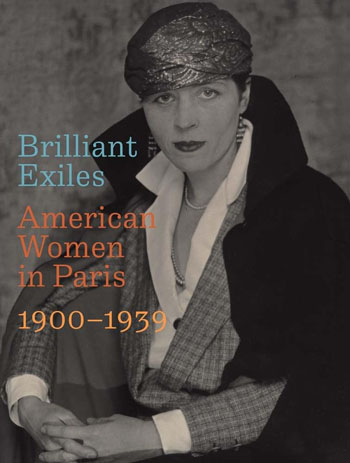

BRILLIANT

EXILES :

AMERICAN WOMEN IN PARIS 1900-1939

Robyn Asleson

Yale University Press. 278 pages. £45. ISBN

978-0-300-27358-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Looking along my book shelves I can see memoirs of what it meant to be an

American or Canadian expatriate in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. Most of

them are by men: Malcolm Cowley, Harold Stearns, Ernest Hemingway, Morley

Callaghan, Harold Loeb, Samuel Putnam, John Glassco. Where are the women? I

have books by and about Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Kay Boyle, Janet

Flanner, but with the exception, perhaps, of Boyle, they don’t seem to have

gone in for autobiographical accounts of what they did, who they met, and so

on. Boyle, when she edited a re-issue of Robert McAlmon’s Being Geniuses

Together in the 1960s, inserted chapters of her own reminiscences of the

period in between his. And Boyle, like a few other women, wrote fiction set

during the expatriate experience. Her Monday Night and Year Before

Last might be relevant in this connection, as might be Djuna Barnes’s

Nightwood. And, though it’s something of a satirical fantasy, Barnes’s

The Ladies Almanack, published in 1928, can be recommended for its

links to the activities of American women in Paris.

But, looking at the list of authors

in the 1932 anthology, Americans Abroad, I count fifty-two names,

only thirteen of which are women.

I’ve

only referred to writers, and the point about Brilliant Exiles is

that it doesn’t only relate to them. Nor does it limit its range to

the 1920s and 1930s, though it could be argued that those years were, on the

whole, the key ones in terms of establishing a narrative of adventurous

American women in Paris. Robyn Asleson points to “a long line of talented,

ambitious American women who crossed the Atlantic during the first

four decades of the twentieth century in search of freedom and opportunities

denied to them at home”. Asleson goes on to refer to, “acceptance of

bohemian nonconformity” and “the mythic stature of Paris as the epicentre of

modern innovation, personal liberty, and cosmopolitan diversity” as aspects

of what pulled women to Paris.

The

possibility of finding the “freedom and opportunities denied to them” in

America was particularly applicable to black women. There is a photograph of

Lois Mailou Jones painting outside a café in 1938 while watched by a crowd

of men: “The half dozen men clustered behind her tilt their heads in rapt

attention, all eyes fixed on Jones’s canvas”.

As Asleson says, while acknowledging that France was by no means

“devoid of sexism or racism”, it’s hard to imagine a similar “encounter

between a Black woman and a group of white men…..in the United States at

that time”. I think Jones must have had some financial support, of one kind

or another, for her Paris sojourn. There is a photograph of her in her

studio and it looks fairly spacious. There was clearly a difference between

Jones’s time in the French capital, and that of Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, a

black sculptor who “endured twelve years of extreme poverty in Paris while

pursuing physically demanding stone and wood carving……Prophet began a

struggle for survival in shabby, unheated studios, often without food or

human contact for weeks on end”. There is a striking and possibly revealing

photograph, taken at some point between 1922 and 1929, which shows an

unsmiling Prophet staring directly at the camera.

If

the black artists were escaping racial prejudice, and the neglect of their

work that went with it, a white painter like Anne Goldthwaite had her own

reasons for believing that Paris had something to offer. She remarked of her

early years in Montgomery, Alabama, “There seemed nothing to do but grow up

and be a ‘young lady’…..I was brought up to believe that matrimony was the

desired end of a woman’s life

and a woman’s career”. Luckily, a sympathetic uncle provided the money for

her to move to New York in 1898 to study painting and etching at the

National Academy of Design. She headed for Paris in 1906, and met Getrude

Stein, and through her was introduced to the work of Cezanne, Matisse, and

Picasso. A self-portrait, painted after she got there, shows a benign,

confident-looking Goldthwaite. Asleson suggests that “Her vibrant technique

resembles the methods of Cezanne and his successors, the so-called Fauves

(wild beasts)”. But if

Goldthwaite was being influenced by radical ideas in art, she didn’t carry

them into her private life. She did go to popular meeting places with

friends (there is a sketch by her of “New Year’s Night at the Café

Versaille”), but “found little satisfaction in attempting to sit with young

men at restaurants”, and had no inclination to “play that I was living in

Bohemia”. It’s of interest to note

that Goldthwaite was represented in the famous International Exhibition

of Modern Art (the Armory Show) in New York in 1913.

Anne

Estelle Rice lived in Paris from 1905 to 1913, and “became a key figure in a

circle of Anglo-American artists developing a modern aesthetic based on the

concept of rhythm”. Rice, like Goldthwaite, had “disappointed her family’s

traditional expectations of marriage and motherhood by embarking on a career

as an illustrator”. She arrived in France on an assignment to “illustrate

Paris fashions for a Philadelphia newspaper”, and “just in time to witness

the furore over revolutionary works of art displayed at the Salon

d’automne”. She was so impressed by the work of Matisse and Derain that she

“took up painting and quickly found success”. Her self-portrait is dated

1909-1910 and indicates how the colour blendings of the Fauves had

influenced her. Rice was the model for John Duncan Fergusson’s “The Spotted

Scarf”, painted around 1908 and well in the style of the “Scottish

Colourists”. Rice had formed a relationship with Fergusson which lasted for

several years. In contrast to Goldthwaite, she took to the unconventional,

exploring “the Latin Quarter’s bohemian haunts, visiting a brothel to see

works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, attending risque events such as the Bal

Bullier, and frequenting the Café d’Harcourt”. She never returned to the

United States. In 1913 she married the English art and theatre critic,

Raymond Drey, and moved to London, where she died in 1959.

There were other women artists, such as Agnes Ernst Meyer (see the

photograph of her by Edward Steichen), and Katherine Nash Rhoades, whose

self-portrait can be compared to the impressive photo of her by Alfred

Stieglitz. She looks somewhat aloof in the self-portrait, whereas the photo

suggests a more-relaxed and open person. Asleson says that, back in America,

“Rhoades helped to establish and operate the Freer Gallery of Art (now the

Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Asian Art) working closely with

Agnes Ernst Meyer, a friend she had met through Stieglitz”.

Not

only writers and artists arrived in Paris. Several black entertainers found

a ready audience there, one of the most famous being Josephine Baker whose

flamboyant dancing intrigued the French and the affluent, white night club

patrons who liked to be seen with her, at least while they were in Paris.

One of the clubs they frequented was Bricktop’s, named for its owner, Ada

‘Bricktop’ Smith and her red hair. Bricktop didn’t just run a night club.

She “served as both anchor and magnet for an expatriate community of African

American women”. Asleson mentions that when Josephine Baker “rocketed to

stardom in 1925, Bricktop took the unworldly nineteen-year old under her

wing”. And “She was waiting at the train station when Florence Mills and the

Blackbirds troupe arrived in May 1926”. She extended a warm welcome to Nora

Holt, Ethel Waters, and many others. There is, incidentally, a splendid

portrait of Waters by Luigi Lucioni in the book, along with a photo of

another black singer, Adelaide Hall, who was popular in Paris.

I

opened this review with some observations about American women writers in

Paris, and it seems useful to take it towards its ending with a few more

comments. Zelda Fitzgerald was always overshadowed by her more-famous

husband, Scott Fitzgerald, but I’ve always thought her novel, Save Me the

Waltz, and her short stories, well worth reading. Asleson is of the

opinion that the novel “offers glimmers of a strikingly individual,

experimental prose style”. Fitzgerald had nursed ambitions to be a ballet

dancer, and her semi-autobiographical book “dwelled on the brutal toil that

enabled the beautiful illusion”. It’s also worth mentioning her

short-story, “A Couple of Nuts”, which has these evocative opening lines :

“The summer of 1924 shrivelled the trees in the Champs-Elysee to a misty

blue till they swayed before your eyes as if they were about to go down

under the gasoline fumes. Before July was out, dead leaves floated over the

square of St Sulpice like paper ashes from a bonfire”.

Caresse Crosby came to Paris with her husband, Harry Crosby, after she had

shocked her family by divorcing her first husband : “Rebelling against their

‘puritanical’ upbringing they pursued a hedonistic lifestyle devoted to

parties, promiscuity, and poetry”. But they also launched Black Sun Press

which published work by Hart Crane, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and many

others. Later, after Harry’s death in 1929, Caresse continued with Black Sun

Press, and additionally started the cheaper Crosby Continental Editions to

bring the work of contemporary authors to a wider audience. A book from this

series that I have and prize is Robert McAlmon’s The Indefinite Huntress

and Other Stories, published in 1932. Caresse Crosby’s The Passionate

Years 1925-1939 tells the story of her adventures in France. There is a

portrait of her by the Belarusian artist, Polia Chentoff, which, to my mind,

does not capture the spirit of the energetic and imaginative woman Caresse

must have been. Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that Chentoff had an

affair with Harry Crosby. Asleson quotes the French poet Saint John Perse,

who said that he had “never seen the distaste of one woman for another so

skilfully and subtly portrayed”.

There is much more to Brilliant Exiles than I have been able to

convey in my review. I have overlooked some of the better-known women, such

as Sylvia Beach, owner of the famous bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, and

Getrude Stein, who has had books written about her and her partner, Alice

B.Toklas. But what of the writer, Mercedes de Acosta, “now remembered less

for her literary accomplishments than for her remarkable life…..In 1921 she

began a passionate affair with the actor Eve Le Gallienne, for whom she

wrote two plays. The most ambitious of these works, Jehanne d’Arc,

debuted in Paris in 1925 – the first instance of an American play performed

on French soil by an American actress speaking in French”. De Acosta was

productive, and “wrote nearly a dozen plays in which women struggle with

‘unhappy marriages, divorce, sexual desire, identity, and self-recognition’

“. Abram Poole painted an imposing portrait of de Acosta. Poole was a

“wealthy society portraitist”, and de Acosta had agreed to marry him “on the

condition that she retain her maiden name and freedom to live an independent

life”.

There is, too, the fascinating Belle de Costa Greene, who could “pass” for

white, as a splendid chalk on paper portrait of her by Paul Hellas

indicates. She was “one of America’s most influential and well-known

librarians”, and travelled to Paris on behalf of the financier, J.P. Morgan.

She spent forty-three years at the Morgan Library and Museum, and when she

retired the New York Times said that “Much that this remarkable

institution today represents can be attributed to the earnest scholarship of

Miss Greene. Her wide-ranging interest in cultural treasures is reflected in

the library’s fine paintings, its unusual collection of illuminated

manuscripts, its rare volumes and letters, its etchings, stained glass, and

pottery”. Reading this, one

might get the idea that Greene was a prim intellectual, but it’s noted that

when she first arrived in Paris in 1910 she was “hungry for an arts

education and eager to meet her lover, the art critic Bernard Berenson”.

With

its wide range of photographs and painted portraits, and its accompanying

informative text, Brilliant Exiles is not only the catalogue for the

exhibition which opened at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington in

April 2024, but also a totally satisfying book in its own right. I have

quoted Robyn Asleson more than once in my review, but it should be noted

that there are, in addition to her contributions, four essays by other

academics with a specialised interest in the subject of how American women

functioned, and how they often related to each other, in the Paris of the

period concerned.