‘OUR LITTLE GANG’ : THE LIVES OF THE VORTICISTS

By

James King

Reaktion Books. 230 pages. £30. ISBN 978-1-83639-055-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

James King, in his introduction to this welcome book, refers to the

Vorticists as a “group of like-minded visual artists”, with Percy Wyndham

Lewis as what might be called their leading light, and Ezra Pound as their

“unofficial promoter”. What kind of “visual artists” were they? King says

that “in its brief existence from 1913 to 1915, Vorticism was the first

attempt by English artists to practice a form of abstraction that was

distinct from all the other manifestations on the Continent”.

But

what was that “form” and why was it distinctive? Here’s one description :

it “combined cubist fragmentation of reality with hard-edged imagery

derived from the machine and the urban environment”. However, King says :

“Vorticism may be a form of Cubism, but Vorticism experimented even more

boldly with colour, employed more angular shapes and distorted spatial

perception more dramatically”. As for the philosophical aspect, King

observes, “By definition, the vortex is a whirlwind, sucking in everything

it encounters, whether animate or inanimate. As a metaphor, the word

describes a world in chaos”. To which can be added Wyndham Lewis’s words :

“At the heart of the whirlpool is a great silent place where all the energy

is concentrated. And there at that point is the Vorticist”. And King again,

“The Vorticist is therefore positioned on the narrow border between order

and chaos…….Vorticist art inhabits a realm where chaotic energy is

harnessed”.

I

don’t want to complicate matters but it has sometimes been suggested that

Vorticism is a kind of English variation of Futurism, a movement largely

originating in Italy and with adherents in Russia prior to the First World

War. Lewis certainly wouldn’t have agreed. King has a useful chapter on

Futurism, and its propagandist, Filippo Marinetti, but points out that, with

the exceptions of David Bomberg and C.R.W. Nevinson, none of the artists

associated with Vorticism displayed a great deal of interest in Futurism.

Its bombast and violence had little appeal in England.

King lists seven artists as central to the Vorticist movement : Wiliam

Roberts, David Bomberg, Edward Wadsworth, Helen Saunders, Jessica Dismorr,

Wyndham Lewis, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. There were a few others who, in

one way or another, were influenced by, or were independently working along

similar lines to the Vorticists. I mentioned C.R.W. Nevinson earlier, and

Frederick Etchells can be seen as having leanings towards Vorticism. His

1914 oil on canvas “Woman at a Mirror” certainly inclines in that direction.

King also brings in Lawrence Atkinson, Cuthbert Hamilton, and one or two

others to fill out the ranks of the Vorticists and near-Vorticists, and

points to the interconnections with Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop. The emphasis

on design at Omega gave some artists an opportunity to put their interest in

abstraction, especially of the geometric variety, to commercial use, where

it could be effective. Shown outside that context, as in a gallery, it

tended to leave itself open to the charge that, to quote an American art

critic, “it belongs to mechanical or ornamental design rather than to art”.

Wyndham Lewis was the towering figure of Vorticism, and it’s difficult to

imagine the movement coming to life, let alone leaving a record in art

history, without his presence. Paintings like the 1914 chalk and gouache on

paper “Red Dust “, and the 1914-15 oil on canvas “Workshop” are, I think,

what Vorticism was about. Even the striking 1921 oil on canvas “Praxitella”,

a “portrait of the film critic Iris Barry”, painted when, to all intents and

purposes, the movement was finished might be seen as still having a link to

Vorticism. King says that it was in 2022 that two students at the Courtauld,

“using X-ray and digital technologies”, discovered that Lewis had painted

over a canvas by Helen Saunders. Reading about his behaviour in general, and

particularly with regard to women, doesn’t exactly make him out to have been

a likeable character.

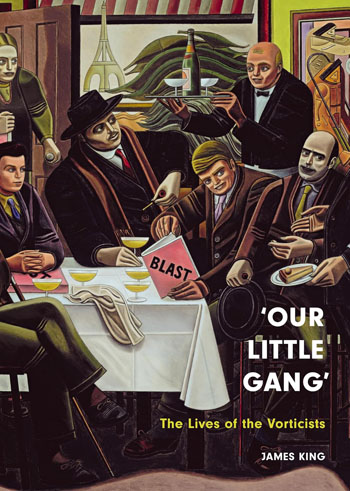

The

front cover of King’s book shows William Roberts’s 1961-62 oil on canvas

“The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, Spring 1915”, and it’s

an illustration used more than once when books about the period are

published. Peter Brooker’s Bohemia in London : The Social Scene of

Early Modernism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) is an example, and, in fact,

is something that can usefully be referred to in relation to the Restaurant

de la Tour Eiffel and the Cave

of the Golden Calf, another establishment favoured by the Vorticists.

Roberts, of course, in 1961 was painting the legend rather than the reality,

though it’s noticeable that the two women in the painting, Helen Saunders

and Jessica Dismorr, are almost there as an afterthought, being placed at

the rear and nearly hidden by the assembled males. That very much was the

reality in Vorticist circles. Roberts always claimed to be a Cubist rather

than a Vorticist, though the insistence on labels can often cause confusion.

His paintings don’t appear to fit directly into the Cubist category, but

they are always identifiably by him. Perhaps he should have been content to

have created a distinctive style and not worried about which group he

belonged to.

David Bomberg didn’t care to be called a Vorticist. As stubborn and

outspoken a type as Lewis, he was volatile and aggressive. Like Lewis, he

wanted to “blow up” the established English art scene. Vanessa Bell

described him as “intolerable” and cautioned Roger Fry against employing him

at Omega. It’s fascinating to see how Bomberg, like Roberts and others taken

on as War Artists, modified his style to suit the requirements for

representational canvases. King tells the story of how Bomberg showed

P.G.Konody (a critic responsible for commissioning artists to work for the

Canadian War Memorial Fund) some charcoal sketches of tunnellers at work

which were modernistic but also clearly realistic. Konody approved of them

but rejected a larger oil on canvas version as a “futurist abortion”.

C.R.W. Nevinson similarly refused the Vorticist tag, though he doesn’t seem

to have minded being labelled a Futurist. King describes him as “very much

like Lewis – a profusely talented, self-assured braggart with a magnetic

personality”. He formed a friendship with the Italian Futurist Gino

Severini, and, as King says, almost immediately made a “remarkable

adaptation… to Futurism”, as can be seen in the 1913 oil on canvas “The

Arrival”, which mixes the abstract and the realistic as the bow of a large

ship appears to cut through the hints of dockside activity. It’s an

eye-catching painting. Nevinson, just as Bomberg did, adjusted his approach

when he worked as a war artist. Recently, I received a postcard from a

friend which was of his 1916 oil on canvas “Dog Tired”, a picture of a group

of soldiers, jackets unbuttoned, sprawled on what look like piles of boxes

and packing cases. It’s an evocative illustration. Weary men, grateful for a

few minutes doing nothing. Nevinson turned away from Futurism after the war,

perhaps because the sights he’d seen were at odds with Marinetti’s

celebrations of machines and noise and violence. For anyone who finds, like

I do, Nevinson’s work of interest, it’s worth looking at David Boyd

Haycock’s A Crisis of Brilliance : Five Young British Artists and the

Great War (Old Street Publishing, 2009) for further information and

insights.

If

Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr were only just in the Roberts group

portrait of the Vorticists, King pays them a little more attention. Both

women seem to have been dominated by Lewis, and it’s likely that Saunders

was in love with him, though her feelings weren’t reciprocated. Kate

Lechmere was another female artist in Lewis’s orbit, but seemingly

strong=willed enough to stand up to him when necessary. She helped Lewis set

up the Rebel Arts Centre, his rival location to Fry’s Omega Workshop, by

providing the money to pay the rent on the premises they used, though when

she could no longer come up with the cash Lewis became abusive.

Lechmere was of the opinion that Saunders and Dismorr were “little

lap-dogs who wanted to be Lewis’s slaves and do everything for him”. Dismorr

came from a wealthy background and Lewis saw her as a source of funds by

buying some of his paintings. When she refused, he fell out with her.

Leaving aside the personal relationships between Lewis and the women, I

found Saunders’ paintings, as seen in the book, of interest, despite my

misgivings about purely geometric abstraction. Her 1915 graphite and gouache

on paper ”Dance” is attractive, while the 1915 graphite, black ink “Black

and Khaki” has a similar appeal. Saunders appears to have eventually turned

away from abstraction, as witness a late-1920s gouache on paper “Still

Life”. It looks pleasant but ordinary. Jessica

Dismorr was initially influenced by the French Fauvists but moved into total

abstraction and continued to associate with various avant-garde groups in

the 1920s and 1930s. King describes her later work as “divided between pure

abstraction and representational works – the latter nodding in the direction

of Surrealism”.

It's obvious that the onset of the First World War in 1914 played a major

role in breaking up the Vorticist group. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, the talented

sculptor of “Red Stone Dancer”, and the painter of a portrait of his

partner, Sophie Brzeska, was French born. When war broke out he returned to

France and joined the French army. He was killed in 1915. Edward Wadsworth,

described by King as “a reticent person”, was “an outstanding student” at

the Slade, where Roger Fry was a lecturer : “Through him Wadsworth became

aware of Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and the other Post-Impressionists”. The

1913 oil on canvas “Rotherhithe” has a clear basis in the real world, but

the 1915 gouache, ink and graphite on paper “Abstract Composition” is

precisely that. Wadsworth was employed on the “dazzle-painting” programme

designed as camouflage to confuse and deter German submarines preying on

convoys.

There were attempts to revive interest in the Vorticist project after 1918,

but its moment had gone. As Francis Spalding put it in The Real and the

Romantic : English Art Between the Two World Wars (Thames & Hudson,

2022) : “artists who had witnessed or been involved in conflict and were

sated with destruction, looked back with incredulity at some of the more

extreme ambitions of the prewar avant-garde; at C.R.W. Nevinson’s claim that

‘there is no beauty except in strife, and no masterpiece without

aggressiveness’ “. Spalding additionally notes : “The fact that piles of the

magazine Blast, in which Wyndham Lewis had published the Vorticist

Manifesto, sat around his studio in the post-war period, unwanted, does not

surprise. Even Lewis himself admitted ‘The geometrics which had interested

me so exclusively before now felt bleak and empty. They wanted filling.’ “

King discusses Blast in his book. There were only two issues, one in

1914, the other in 1915, before the war claimed the time and energies of

many of the contributors. It’s instructive to look at the magazine’s

contents and in particular at Lewis’s pronouncements about upsetting the

apple cart of not only the English art establishment, but English society

generally. “BLAST First (from politeness) ENGLAND : Curse its climate for

its sins and infections”.

Quoting it this way doesn’t recognise the perhaps startling visual effect it

may have had at the time, though I do wonder how many people actually did

see the magazine? Spalding’s comment about all those unsold copies in

Lewis’s studio is relevant.

Beyond the handful of leading Vorticists, as defined by King, he brings in a

host of others who were involved. Ezra Pound (he originated the “Our Little

Gang” description) is there, as is

T.E. Hulme, described as “the theorist” and sadly killed in the First World

War. And there are references to Walter Sickert, the Camden Town artists,

Jacob Epstein, and many more. King quite correctly puts the Vorticists in

context. They were not operating in a vacuum, and what they were aiming for

only has relevance if seen in relation to other work of the period.

‘Our

Little Gang : The Lives of the Vorticists tells a stimulating story,

told by James King in a clear and direct way.

His writing is intelligent and steers clear of art jargon and

theorising. He outlines the personalities and their differences, which

inevitably in any community inhabited by competing egos, were frequent and

not unusual, but always places the art at the centre of his narrative. His

book will appeal to those with a specialised interest in the development of

avant-garde painting in England, but also to the general reader of art

history. It is well-produced, is liberally illustrated, has notes, and a

bibliography.