|

Desperate Vitality

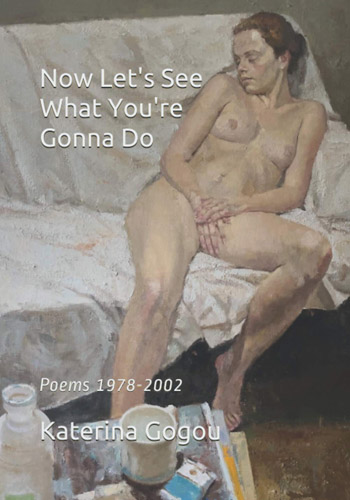

Now Let’s See What You’re Gonna Do: Poems

1978-2002 Katerina Gogou Translated by A.S. Introduction by Jack

Hirschman. FMSBW – Divers Collection, 2021

ISBN-13:978-1-736264-5-0

Poet and actress Katerina Gogou is a figure

better known in anarchist circles than in the literary world. This

collection of her poems (almost her entire poetic output) is the

first in English to appear since Jack Hirschman translated and

published her first collection back in 1983. The title of this

initial collection ‘Three Clicks Left’, referencing the technique of

aiming a machine gun, gives some indication as to the milieu that

Gogou belonged to. Born into Nazi occupation and living under the

Greek Junta she began writing poetry in the late 70s, a time that

saw an upsurge in university and factory occupations spurred on by

the Athens Polytechnic uprising of 1973. Yet, as many know,

anarchism is not just a matter of politics pure and simple, of

insidious party machinations and soppy paeons to an heroic working

class. It is not about didactic propaganda and objective conditions,

it is about a way of being, a way of life. And so, Gogou, on the

suspect list of the Greek Ministry of Public Order, was a prime

mover in the Greek counter-culture of squats and communal living

that centred on the Exarchia area of Athens. She frequented the

“hard luck dives”, hung out with the “damned of the metropolis” and

participated in a musical culture that included the underworld

soundtrack of rembetika (‘passion-drugs-jail-death’), the

‘concert riots’ of the 70s and benefit gigs for arrested anarchist

and transexual militants who had been exiled to island-gaols. Indeed, as an actress, starting out in the

comedy genre and often being cast as the ‘rascal pupil’, Gogou had a

leading role in a film with a strong musical theme. Parangelia,

a Greek cult classic, casts Gogou as a night club singer (more Nico

than Cleo Laine) who not so much transcendently narrates as

poeticises-over the unfolding of an underdog tragedy (the last night

of the outlaw Koemtzi brothers). Gogou’s role in the film is that of

a one-woman Greek chorus. Poems from her first collection are

impactfully recited direct to camera throughout the film. Her

opening lines are as follows: “I want to talk with you in a café where the

door would be wide open and there’d be no sea These latter lines reference the opening

sequence of the film. As the credits roll, Gogou applies her make-up

and we witness her preparing herself for the glamour of the

dressed-up night life. However, there soon flickers across her face

subtle looks of a rising despair and an implosive self-loathing

before she angrily smears-off her lipstick and rubs at her mascara

eyes as her tears begin to fall. In her acting of this sequence, as

with her poems, we are witness to what Pasolini has called a

“desperate vitality.” At times in the film Gogou’s recitation raises

to a crescendo of an un-affected, almost unacted, cry of anger that

brings to mind the punk vocalist style of the day as well as the

infamous recording of Artaud’s ‘To have done with the Judgement of

God’. Safe to say in Gogou’s poetic world there is no God,

apparatchiks or idealised revolutionary subjects. Maybe we could

venture to say there is no poetry here either!

Just as musicians from Charlie Mingus to Cecil

Taylor remarked: ‘What the fuck is jazz?’ We could similarly ask,

when confronted with these journal-like and at times utterly candid

pieces of writings: ‘What the shitting-hell is poetry?’ There is

thus an anti-literary tenor to much of her writing which she

directly refers to as “scribbling on papers.” (p.66): “Rotten / Rotten themes/ mouldy volumes devious

libraries Words and the various motivations in yielding

them are placed under a painful suspicion that only the sincerity of

affectable bodies can alleviate. Gogou, as a writer informed by

acting, is the non-discoursing body that Pasolini honours; a

revolting body mutating under the dictates of a consumer inducing

narcissism that, as in the opening sequence of Parangelia,

she both embodies and expels: “how harassed we’ve become by guilt,

shop windows and bald manikins/ but no longer with bowed heads”

(p.61). These links to the much-indicted Pasolini are not fortuitous

as Gogou, who rarely gives titles to her writings, does title one

piece, “Autopsy Report 2.11.75”. This is a reference to the

assassination of Pasolini and the multiple injuries he received in

the wastelands of the Ostia Basin. Here the foretold mutilated body

takes centre stage but Gogou is not rendered speechless. She does

not theorise but pens a sequence of barbs that reveal that there is

strength in her disenchantment, a strength to call-out the endless

historical compromises: “… the body lay face down in parallel

connection to the Vatican Another factor that sees Gogou linked to

Pasolini has been encapsulated by one commentor on the Blackout

website (see references below) who describes her writings as a

“cinematic record of reality”. This is akin to what Pasolini pursued

across his poems, novels, films and journalism as the “written

language of reality.”

Not only does this shed light on Gogou’s almost diarist style, it

places her in the realm of a new hybrid form that Pasolini was

outlining. The screenplay not simply needing completion by being

filmed but the screenplay as a written and embellished form in its

own right (Benjamin Fondane’s Cinepoems spring to mind in

this connection). One could say Gogou, an actress familiar with a

cinematic means of production, is under the influence of a filmic

aesthetic and rather than embroider screenplays she embellishes the

private ‘note-to-self’ form (an object of ridicule in poetry

circles) in which a deliberate unfinishedness articulates a

processual rather than reified approach to living. Above all else it

seems Gogou was not identifying herself as a poet: “What I’m afraid of most of all is lest I

become a ‘poet’ […] Form can be mediational, it can defuse the

offer of direct communication, leave unsaid what Pasolini calls the

“profound intimacy of the individual”. There is a ‘beyond’ of poetry

just as there is a cinema that can be inflected with the poetic

impulse. So, Gogou seems to owe a lot to a cinematic revisioning of

poetry; cinema as a refreshing means to approach language anew: her

extended lines are akin to long shots, her short two-to-three line

poems are like celluloid scraps gathered from the cutting-room

floor, her stuttering fracturing of images are akin to rapid

jump-cuts … a kind of holistic concatenation: “abortions

bottles mirrors movie programs my friends’ personal lives.” (p.63) So, montaged flows. Long shots telescoping

history and at the same time closing-in on memories of the nights

before. Revolutionary regret spliced with confessional soliloquies.

A redemptive abjection: “poetry has ceased madness slips out” (p.84)

A hatred of the system as virulent and deadly as that which the

Greek post-dictatorial democracy reserves for the conveniently

unrepresentable wretched of the earth: no party’s canvassing object.

Words all tangled-up (p.89)

In writing of Pasolini as he could have been

writing of Gogou, René Schérer offered that “to become revolutionary

is to enter life. By flashes. To have an intuition, beyond all

political logic and reason.” One could add that, as an anarchist to

the end, harassed by the police for her friendship with Athenian

extra-parliamentarians and ex-cons, Gogou, who suicided in 1993, was

one who knew that there would be a recomposition of class beyond the

“threadbare ideologies” (p.76) of anarchism and communism; a

recomposition that would entail the coming-into-being of what Walter

Benjamin, referencing Charles Fourier, named an ‘affective class’.

Above all, the recomposition of subjectivities not as individuals

but as singularities for whom poetry is not so much a con-trick

craft as a means of everyday intensification: “I am dreaming

freedom/ Through everyone’s/ all-beautiful uniqueness.” (Coda) The time of the oeuvre has

long-gone and, in order to not acknowledge this, to continue-on

deluded, countless prizes are dutifully handed out to those poets

who maintain the myth of a bygone tradition.

Howard Slater References The Blackout ((Poetry and Politics)) blog

features a sample of poems by Katerina Gogou and biographical

details.

https://my-blackout.com/2018/01/21/katerina-gogou-autopsy-report/ Pier Paolo Pasolini: Heretical Empiricism,

New Academia Publishing, 2005. René Schérer: Des modalités du ressentiment

dans les devenirs révolutionnaires, in Chimeres No.83, 2014

https://www.cairn.info/revue-chimeres-2014-2-page-71.htm

Taxikipali: Katerina Gogou Athens’ Anarchist

poetess, 1949-1993. This article mentions a biography of

Katerina Gogou by Agapi Virginia Spyratou entitled Katerina

Gogou: Death’s Love [Erotas Thanatou], Vivliopelagos, 2007. See:

https://libcom.org/article/gogou-katerina-athens-anarchist-poetess-1940-1993

|