|

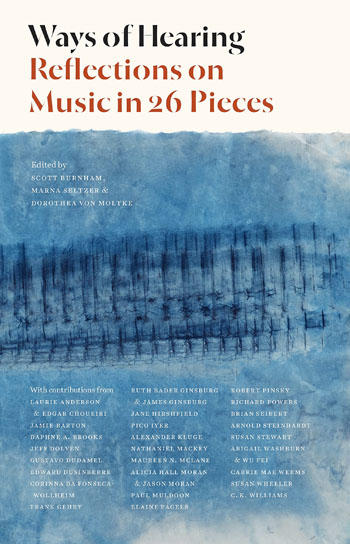

WAYS

OF HEARING

Reflections on Music in 26 Pieces

Eds Scott Burnham, Marna Seltzer & Dorothea von Moltke

ISBN 978-0-691-20447-5

The best pieces in this book are by professional musicians, which is

predictable: take a person away from their expertise and they are an

idiot. Gustavo Dudamelís essay on Fidelio, for example, is a

little masterpiece. You would need to be well trained in music to

grasp its details, which is perhaps a problem in writing about

music. There is an entire industry devoted to writing about what is

associated with music, especially pop. You could fill a library with

books about The Beatles, but most of them have nothing to say

about music and are probably written by people who donít have the

skill. Most of the music discussed here is of the kind people listen

to rather than through. No one, presumably, ever played air cello.

The pop variety is a muddled form in which the music serves group

identification and narcissistic propping of unsure minds. To write

properly about music you need to know how it works, and few of us

do. When Dudamel writes that Beethoven had ďthe timpani tuned in

tritonesĒ only a minority will grasp what that means and its

implications. Yet itís precisely because, as a non-musicologist

reader, you realise you are in the company of an expert, that the

best writing here is so pleasing.

Perhaps the book is aimed at a musically sophisticated audience.

That would be a pity. Itís a fine thing to put highly skilled work

in front of a much less competent audience. The notion of pearls

before swine implies the majority can never be anything but swinish.

Like Dudamel, Edward Dusinberre carries his talent naturally.

Driving to a recording on a winterís morning, he listens to and

muses over Schubertís String Quartet: ďWhile the second cello

continues its pizzicato frame and the inner voices journey through

their chord changes, I am propelled to the second and fourth beats

of each bar by a simple dotted rhythm.Ē Most listeners, even to

serious music, probably pay most attention to their emotional

response, music having the advantage over language that it can go

straight to the emotions without having to be filtered by the

nuisance of semantics. To be made aware of the kind of listening an

expert musician engages, is an encouragement to find out more.

Jamie Barton impels in the same direction. She explains how

enraptured she was on first hearing Chopin and, tellingly, how

Claudio Arrauís interpretations seem to her most in keeping with the

composerís music. Thatís a good lesson in listening and thinking

carefully. Charmingly, she relates how a compilation CD, Chopin

and Champagne, changed her life. The title might seem cheap and

commercial but the artists certainly werenít: Arrau on all but one

track and the London Philharmonic. Perhaps thatís a good reminder of

how people can be inspired to a love of the arts in the most unusual

ways and how we should encourage whatever interest people show

without being judgemental.

Abigail Washburn and Wu Fei have in common both music and familial

similarities, not all of them positive. Their contribution is a

fascinating exploration of communication across cultural

differences. The identity they discover in two apparently

unconnected songs is a reminder of our common human inheritance, of

how little comes between us in spite of superficial distinctions.

Music, of course, is universal. Not in the same way as language

which is an inherited faculty present in all of us (barring fairly

severe damage). Not everyone is musical, but all cultures are and

there seems to be evidence for a more or less universal response to

music of certain kinds, even in people who canít hold a tune.

Arnold Steinhardt focuses on Beethovenís String Quartet in B flat.

Heís excellent on the nature of the string quartet as a form and

enlightening on details about his chosen one: how, for example, in

the Cavatina movement, a very unusual key change generates the acute

sense of someone who is ďbeklemmtĒ (anguished). He quotes Einstein

who said things must be kept as simple as possible, but no simpler.

Steinhardt sees that simplicity as the core of string quartet, a

true musicianís insight.

The least successful pieces are probably those from poets. Poetry

can be about anything of course, but in company with people who know

music inside out, the poets seem somewhat out of place. Paul Muldoon

contributes a piece on Elgar. The rara avis always was in fact quite

commonplace. In response to his famous question, it could be said

though the poem purports to be about Elgar, itís really about

Muldoon.

There are one or two references which might seem somewhat dubious.

Elaine Pagels writes of her love for Elvis, but perhaps youthful

indiscretions can be glossed over. Pico Iyer praises Leonard Cohen

whose songs are surely put in the shade by those of Georges Brassens

who Laurie Anderson and Edgar Choueiri wisely include amongst their

favourites.

Jeff Dolven makes a mistake in his piece, Work Song: it was

Baudelaire not Stendhal who said that beauty is the promise of

happiness; and there is an interesting reference to evolution and

mathematics in Alexander Klugeís essay on opera. The mathematical

faculty canít be an adaptation because the majority of people whoíve

walked the planet have never used it, but then nor can musical

ability but look what joy that brings.

|