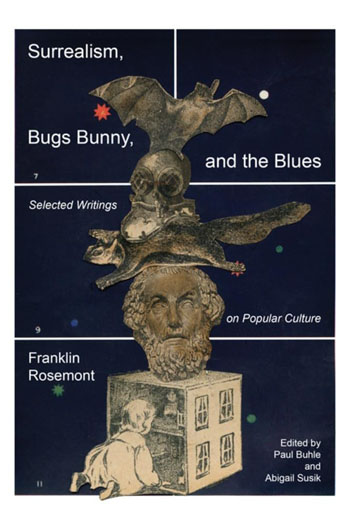

SURREALISM, BUGS BUNNY, AND THE BLUES : SELECTED WRITINGS ON POPULAR CULTURE

By

Franklin Rosemont (Edited by Abigail Susik and Paul Buhle)

PM

Press. 348 pages. $26.95. ISBN 978-8-88744-092-7

Reviewed by Jim Burns

It

might be useful before starting this review to say a few words about

Franklin Rosemont. He was born in 1943 in Chicago. His father was a

typographer and labour activist, and his mother “a professional musician

(accordion, piano, vocals), and leader of the Sally Kaye Trio”. She was also

“the onetime ‘Boop-boop-a-doo girl’ of the Chicago Theatre and star of ‘The

Streets of Paris’ at the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair”. Rosemont “grew up in

and around Chicago, home of the blues, non-cinematic gangsters, the

Haymarket anarchists, the Industrial Workers of the World, the Water Tower,

and the Maxwell Street Market”. In an autobiographical fragment he tells us

that, “Armed with Zen lunacy, Nietzsche, Rimbaud, and the first glimmers of

the surrealist adventure, I dropped out of high school and hitchhiked west”,

ending up in San Francisco. That was in 1960 and the Beats were then in the

news. He eventually headed back to Chicago, which became his home and base

for his activities, including writing, publishing, and much more.

Surrealism, Bugs Bunny, and the Blues offers a sampling of the range of

Rosemont’s interests and involvements.

It's worth noting that Rosemont’s devotion to the Industrial Workers of the

World (IWW) was a major factor in his thinking. Abigail Susik, in an

informative introduction, says that he “joined the IWW in 1962, quickly

receiving his red membership card and becoming a regular at the union’s

international headquarters in the Lincoln Park neighbourhood of Chicago.

Soon acquainted with the older generation of Wobblies – the popular nickname

for members of the IWW – who frequented the headquarters, Rosemont was not

long in emerging as an expert on the vivid IWW culture of direct action and

decades old vernacular archive of satirical cartoons and rousing songs

related to rebel folklore”.

It's easy to see what Susik was referring to by reading Rosemont’s “A Short

Treatise on Wobbly Cartoons”, a fact-filled and well-illustrated piece that

he wrote. As he said, “the Industrial Workers of the World always was more

than a union……its social/economic revolutionary perspectives were broadened

and deepened by a no less revolutionary cultural dimension……the IWW made

history not only on the job and in the jungles, but also in poetry, fiction,

theatre, and the graphic arts”. Rosemont further pointed out that the

graphic arts “remains perhaps the least studied realm of Wobbly culture”.

And, “Few historians of cartooning have been interested in labour, and even

fewer labour historians seem to be interested in cartooning”. He does draw

attention to Joyce L. Kornbluh’s wonderful Rebel Voices : An I.W.W.

Anthology (University of Michigan Press, 1964), which brings together

poetry, prose, and illustrations from Wobbly publications, including what

Rosemont refers to as cartoons.

It

needs to be said that much of what appeared in IWW magazines and newspapers

was produced by rank-and-file members of the union. There were few

professional writers and illustrators among them, though that, in a way,

helped to give their work an immediacy that a more sophisticated approach

might not have had. Wobbly cartoons made direct references to working

conditions, strikes, and similar matters. Bosses, policemen, and politicians

were usually shown as bullying and corrupt and nothing good was likely to

come from them. The cartoons admittedly varied in terms of the quality of

artistic achievement, but that wasn’t the point. The aim was mostly to make

uncomplicated visual statements lampooning those in authority and

highlighting injustices. Some did display an awareness of the kind of art

being produced outside the labour market – Rosemont refers to a possible

influence from Upton Sinclair’s 1915 The Cry For Justice, which had

illustrations by Walter Crane, Kathe Kollwitz, Theophile Steinlen, and other

artists of social protest. It’s a personal recollection but I was always

pleased that, about fifty years ago, I contributed a few things to The

Industrial Unionist, a magazine published by a small British branch of

the IWW, including the words for a cartoon strip.

It's probable that some ideas were picked up from cartoons published in

widely read newspapers and popular magazines. In fact, Rosemont shows how a

number of well-known cartoonists whose work appeared in established

publications like The New Yorker also contributed to radical outlets

such as New Masses and the Daily Worker. An example might be

Syd Hoff. His socialist cartoons were reprinted in 2023 in The Ruling

Clawss by the New York Review of Books. (See my review in The

Northern Review of Books, June 2023). Hoff used the name A. Redfield

when contributing cartoons to left-wing magazines.

Rosemont is entertaining and provocative when he looks at widely popular

cartoon characters such as Bugs Bunny and Krazy Kat: “Bugs Bunny (whose

ancestors include Lewis Carroll’s eccentric White Rabbit and the psychotic

March Hare) is categorically opposed to wage slavery in all its forms”. His

enemy is Elmer Fudd, “a bald-headed, slow-witted, hot-tempered bourgeois

dwarf with a speech defect, whose principal activity is the defence of his

private property…..the perfect characterisation of a specifically modern

type: the petty bureaucrat, the authoritarian mediocrity, nephew or grandson

of Pa Ubu. If the Ubus (Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin) dominated the period

between the two wars, for the last thirty years it has been the Fudds who

have directed our misery……Almost alone against them all, Bugs Bunny stands

as a veritable symbol of irreducible recalcitrance”.

As

for Krazy Kat, the cartoons are “before all else a poetic work, and George

Herriman is one of the greatest American poets……Krazy Kat is

definitive proof of our oft-reiterated contention that American poetry in

this century has lived primarily outside the poem”. Rosemont refers

to a “riot of rhyme and ‘reasons beyond Reason’, and therefore situated

outside any traditional discipline…Krazy Kat drinks from sources

deeper and more far-ranging than philosophy or religion. ‘The world is as it

is, my dear K’, Ignatz explains, ‘is not like it was, when it used to be’.

To which Krazy responds: ‘An’ wen it gets to be wot it is, will it?’ “.

It

may be of interest to note Rosemont’s comments on Robert Warshow’s

interpretation of the Krazy Kat cartoons. Warshow wrote on aspects of

“popular culture” for magazines like Partisan Review and

Commentary in the late-1940s and early-1950s. But Rosemont clearly

didn’t agree with his view that “Herriman’s strip is without significance

except perhaps as a symptom of ‘the extremity of….alienation’ in ‘Lumpen

culture’”, and added, “Behind this abstentionism we cannot miss the

ill-concealed sneer of the snob”, who condemns something with faint praise

because it is “outside the

purview of High Culture……Warshow typifies the unhappy bourgeois intellectual

who would choose at all costs to remain unhappy rather than cease to be

bourgeois”. I have to say that Rosemont had a forceful line in invective. At

one point in an essay about Frank Belknap Long, a writer who might be known

to readers of “fantasy novels, science fiction, gothic romances”, but not

many others in this country, he refers to Norman Mailer as a “ludicrous

mediocrity” and Allen Ginsberg as a “groveling imbecile”. To be honest, I’m

never sure what useful purpose that sort of abuse serves, other than to make

its originator feel good. But to return to Warshow, I have to say that he

has always struck me as a more interesting writer than Rosemont suggests.

His collected essays in The Immediate Experience : Movies, Comics,

Theatre and Other Aspects of Popular Culture (Harvard University Press,

2001) are worthy of attention. Compared to other New York Intellectuals he

was trying to show that what is known as “popular culture” has its values,

even if he didn’t necessarily go along with Rosemont’s view that it might be

more important and relevant than much so-called “High Culture”.

I

have to admit that it’s been hard for me to be detached while writing this

review. So much of what Rosemont writes about seems to have been part of my

own interests and experiences, in particular surrealism, the IWW, and bebop.

Rosemont says “The passage of time has not in the least diminished the

radiant glory of bop, which on the contrary extends each day…..The luminous

integrity of this music – and therefore of the musicians who produced it –

stands in striking contrast to various murky, commercial rationalisations

and debasements that came after….surrealism and bop were rallying points of

human freedom. Inevitably they were attacked by all forces of

reaction….neither surrealists nor bop musicians were allowed to prosper. The

magnitude and magnificence of their achievements appear all the greater in

view of the impossible odds against them”.

Rosemont goes on to assert that the blues “is the basis of jazz”, according

to Charlie Parker, and this points to his own love of the music of Blind

Lemon Jefferson, Elmore James, Big Joe Williams, Roosevelt Sykes, and others

who were, for him, “ ‘alchemists of the word’ directing their incantations

against the shabby confines of a detestable ‘reality’ “. Again, I have to

disagree a little with Rosemont when he contrasts bop and the blues to what

he describes as “the soothing, muted, sterile sounds of Stan Getz and Chet

Baker”. Their music had its attractions, and Charlie Parker thought well

enough of Baker’s playing to hire him for gigs in California.

With regard to surrealism, Rosemont, though obviously fully aware of its

history and its theories (Andre Breton is listed numerous times in the

index), didn’t confine his interest to the past. He looked for it in comics,

films, Charles Addams’s cartoons, and “writers who were ‘surrealists in

spite of themselves’ “. Pulp novelists like Fredric Brown (Night of the

Jabberwock) were in this category. And it’s easy to see why the novels

and stories of H.P. Lovecraft would have attracted Rosemont’s attention. Did

he know the writings of William Hope Hodgson? I hope so. Hodgson was killed

in the First World War, but his The House on the Borderland, Carnacki the

Ghost Finder, and The Ghost Pirates were works of the

imagination, and are still reprinted. And surely he would have been aware of

the great English anonymous poem, “Tom O’Bedlam”, surreal yet dating from a

time long before the word “surrealism” existed. Abigail Susik’s introduction

is sub-titled “Franklin Rosemont’s Search for Surrealist Affinities” and is

a useful guide to how he saw surrealism as a serious issue in his approach

to social and cultural questions.

The

IWW always interested me from the moment I first came across a brief mention

of the organisation in James Jones’s novel, From Here to Eternity.

That was in the early-1950s when I was a young soldier in the British Army.

When I left the army in 1957 I started to find out what I could about the

Wobblies and soon realised that, although they were a union, their aims and

interests went beyond the usual focus on wages and conditions : “Wobblies

made no secret of the fact that they wanted ‘more of the good things of

life’ for the workers of the

world, and that among these ‘good things’ were the fine arts that the

bourgeoisie had appropriated for its own exclusive enjoyment”. During the

1912 Lawrence Textile Strike the young mill girls carried a banner reading,

“We want bread and roses too”. The slogan was later incorporated into a

poem, “Bread and Roses”, by James Oppenheim, who was also the author of

The Nine-Tenths, a novel in which a fictional work-place fire is based

on the real fire at the Triangle Waist Company in 1911, “in which 146

workers, chiefly young girls, burned to death because the sweatshop doors

were locked”.

Rosemont tells us, “Many of the several dozen old-time Wobblies I have known

have been authentic working-class intellectuals – self-taught,

independent-minded men and women of considerable culture, frequenters of

libraries and art museums, with extensive knowledge of poetry, philosophy

and painting”. He quotes Kenneth Rexroth, ”a modernist poet and painter who

himself carried a red card in those years”, on the subject of the Radical

Bookshop in Chicago which “imported the avant-garde poetry of the Twenties

from France and Germany and Russia”.

Anyone wanting to follow-up on Rosemont’s views on the significance of the

arts within the IWW ought to read his Joe Hill : The IWW & the Making of

a Revolutionary Workingclass Counterculture (PM Press, 2015) and his

Rise and Fall of the Dil Pickle Club : Chicago’s Wild ‘20s (Charles H.

Kerr Publishing, 2013). A lot of the poetry, prose and other material

written by Wobblies was ephemeral and only exists in old magazines and

newspapers, but just from my own bookshelves I can select Bars and

Shadows : The Prison Poems of Ralph Chaplin (Allen & Unwin, 1922) and

Charles Ashleigh’s Rambling Kid (Faber, 1930), a novel based on his

years with the IWW. Ashleigh was British born, and was deported from the USA

after being imprisoned at the time of the mass trial of Wobblies in 1918.

Back in Britain he joined the Communist Party. There’s also Arturo

Giovannitti’s Poems (Ediciones el Corno Emplumado, 1966), an

English-language edition of his poems published in Mexico.

Franklin Rosemont died in 2009. There is more in Surrealism, Bugs Bunny,

and the Blues than I’ve been able to indicate in this review.

Rosemont writes about Edward Bellamy and Looking Backward, Radical

Environmentalism, The Image of the Anarchist in Popular Culture, the Jimi

Hendrix Experience, Black Music and the Surrealist Revolution, the legendary

Wobbly writer T-Bone Slim, and more. Rosemont shared the Wobblies

“implacable disdain for the pretensions of all ‘leadership’ “, and their

“mistrust of – and hostility towards – capitalists, cops, and preachers”. It

came through in his writing. He had a regard for culture and learning, but

not for the ways in which they were used by those in authority. He was a

writer with a lot to say and a lively way of saying it.