INSTANTANEOUS MUSICAL DRAMA[1]

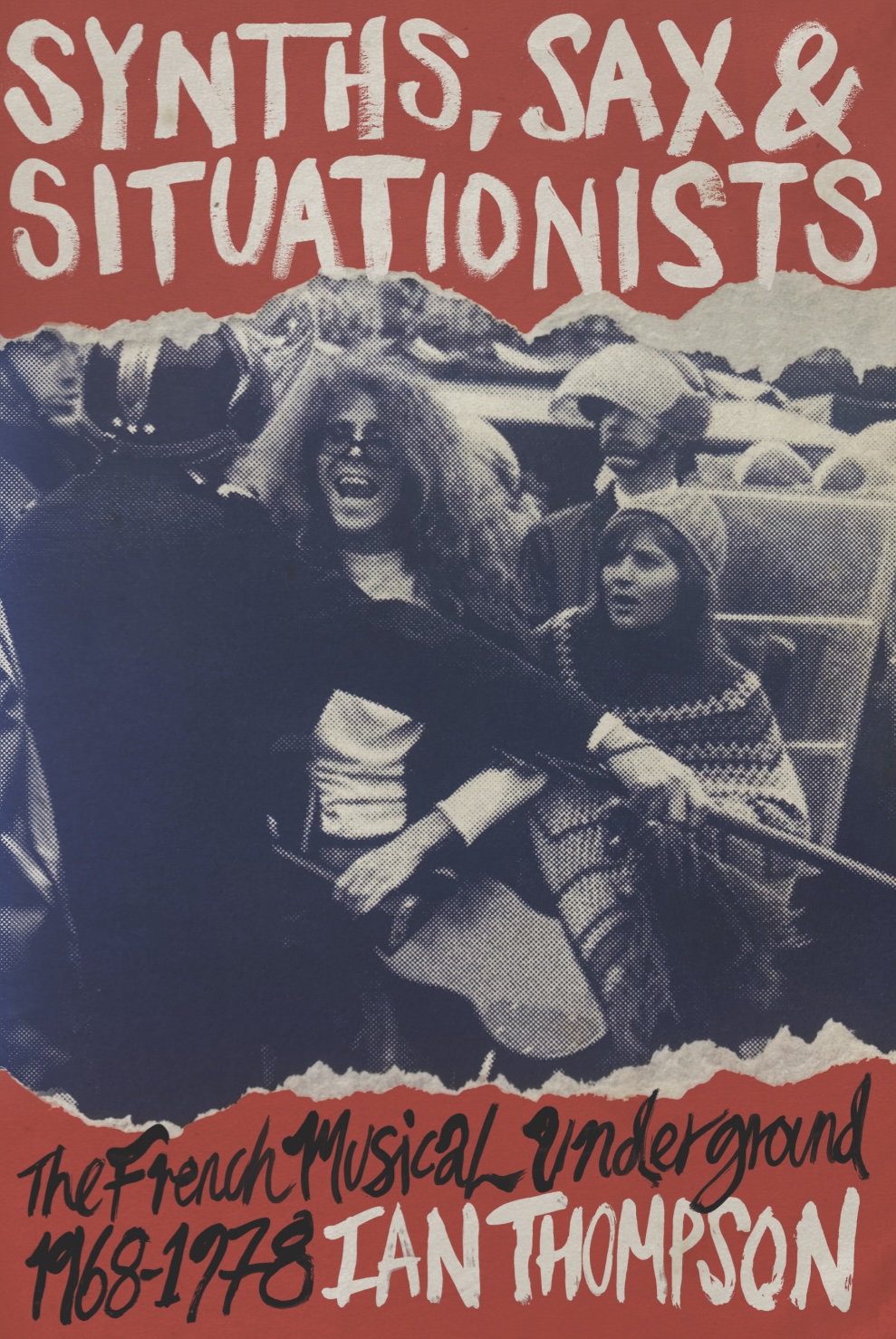

Synths, Sax & Situationists: The French Musical Underground 1968-1978

Ian

Thompson

We have always experienced our music as a war machine,

pure sound, which aims to shatter certain lines

of permanence to put in

place pure intensities...

-

Richard Pinhas (Heldon)

Flashback to the late 70s and a coming to musical consciousness. A time when

continental Europe seemed far away for many working-class families despite

those holidays in the sun that the Sex Pistols lambasted. A school trip to

France was to journey to the other side of the world, but only to be

initiated into getting drunk, visiting chateaus and roaming the streets of

Pigalle. Return to this time, as punk rock opened many peoples’ ears, and

the only French music on our foreclosed horizon was the pop-puppet Plastic

Bertrand (who probably propelled the term ‘plastic punk’ of which there were

many as the major labels went into manufacture mode.) Yet, there were soon

clues that should have been heeded. Manchester’s Factory label had a sister

label called Factory Benelux (an almost incantatory word this Benelux…

beneficent luxury etc), their bands played in places like Groningen and

Tielt and the first release on sister independent label, Rough Trade, was by

a French punk outfit, Métal Urbain. Despite these clues, there was still a

sense that, as far as music was concerned, the Anglo-American sound, be it

rock or pop (jazz was then just dad trad), was the weltanschauung and

any other musics were laughable imitations. Thus began the struggle to break

away from what could be called a monopolising cultural protectionism. For

many the first stop away from nationalised normalisation and genre-capture

was the underworld sleaze-drone of many Velvet Underground tracks.

Perhaps the first sonic winds from continents other than the Anglo-Saxon

ones came with the sounds of reggae and dub that burgeoned alongside punk,

but, in terms of rock, our punk heroes, despising the Stones and Elvis,

began to mention bands like Can and Amon Düül which opened us up to a whole

zone of experimentation dubbed ‘krautrock.’ To this day, perhaps, the

influence of bands like Faust and Cluster, especially on the rise of

electronic-based ‘industrial’ music in the early 80s, has not been fully

appreciated. This is probably due to bands such as these being associated,

somehow, with the category of ‘prog rock’ which became a bête-noir

for punks and post-punks (Yes, Genesis etc). But as with any musical

category, it proves a securitising conditioning tool for generalising-away

whole swathes of possible sensuous learning and reduced the possibilities of

sound to the signature brands of the most successful bands; which, as is

well known, are often the ones that, hyped-up, sell the most units. So, Ian

Thompson’s book is a welcome addition to the musical archaeology genre that

not only does for French underground music what Julian Cope’s

Krautrocksampler (1995) did for those Kosmische musicians based

in Germany, but, furthermore, it contextualises this underground as having

roots in the political coming-to-consciousness, the cultural free-for-all,

of May ‘68 as this coincided with the arrival on the French festival scene

of free jazz outfits like the Arts Ensemble of Chicago (AEC) and dissident

classical musicians like those grouped as Musica Elettronica Viva.

If

May ‘68 is seen as the province of the Situationist International (SI) then

this is by no means universally accepted. Whilst it is undoubtable that, as

they said, “situationist ideas are everyone’s heads,” and that they coined

many of the memorable slogans of the period that resonate to this day, there

is also the sense in which the SI came promote themselves as crucial to the

times. Whilst this is something of a poison chalice in that May ‘68

‘failed,’ it is also a testament to their lust for historicization that, to

a degree, helped their longevity despite the existence other revolutionary

theoretical currents (for example Le Mouvement Communiste and

the Italian operaists) and counter-cultural scenes (2nd

Situationist International, Living Theatre, Kommune 1.) An instance of this

bid for predominance, that runs counter to the communal ethos and sonic

exogeny of many of the bands covered in Thompson’s book, is a scene in the

film version of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, where he

highlights his own head with a white circle so that his presence can be

evidenced in amongst a sea of others gathered there in the Odeon Theatre.

Whilst Debord went on to scorn the ‘pro-situs’, the musical agitators that

feature in this book could be said to have continued “creating situations”

and, in many instances (Barricade, Red Noise, Lard Free and Camizole) were

wary of the commodity-form by neither rushing to produce singles and albums

nor concerning themselves with turning their creativity into archival

objects. This hints at one of the elements that marks the ‘Political

Underground’ and ‘Avant Underground’ sections of this book: a marked sense

of ‘instantaneous musical drama’ made by often fledgling musicians using all

manner of instruments in groups of shifting membership (upwards of eighty in

the early days of Camizole). This paradigm-defying approach to sonic

agitation has striking similarities with the UK’s Scratch Orchestra, a

roving band of musiking troubadours, whose sound was once described

as “devastatingly amorphous.”[2]

Thompson cites the following review of a gig by Camizole that featured in

Liberation: “In the middle of the drum ‘solo’, firecrackers go off at

our feet, hubcaps are randomly thrown onto the cymbals disturbing and

inspiring the drummer. The tenor saxophonist wanders into the hall playing,

waits while two concealed speakers spew out synthesiser, then responds with

a long free improvisation that breaks off at the point of physical

exhaustion... Saxes, violin, synth, guitar and drums are thrown together so

violently and intensely that it can’t be expressed in words... Their music

lies far beyond the commonplace imagination; it’s no longer art reserved for

and performed by an elite, it becomes an extension of communication where

everyone has to participate.” Whilst this is not indicative of all the bands

that Thompson features (there are sections on the lysergic, jazz and

electronic undergrounds) we do get a sense here of the underground as

extolling collective participation that not so much leads to aesthetic

objects of contemplation as to a messthetics, that, as the sound of a

crowd, eschews ideas of exclusive and learned access, and exceeds the

purview of bourgeois art, which, today, lives on as the sonic art and

over-tutored composition purveyed by Radio 3’s Late Junction and New Music

Show.

Whilst Debord was rumoured to be into free jazz there is very little in the

SI’s oeuvre to base this upon. Like the Parisian Surrealists before them

they went cold before sonic experimentation or, as documented in this book,

they had little direct interest or even remote links to L’agit-pop as

it was termed by commentators in the early 70s.[3]

This may seem strange as, with a hindsight enabled by research like that of

Thompson’s, there is a good case to be made that the French musical

underground at this time, as elsewhere, was “realising and supressing art”

as the SI once called for, and which Asger Jorn, translating from the

Hegelian, once fleshed-out as the “open creation.” That said, Debord became

involved in an editorial capacity at Editions Champs Libre, and may very

well have been closely involved in the publication of Free Jazz/Black

Power by Philippe Carles and Jean-Louis Comolli. This book, translated

into English in 2015, is a forceful historical and materialist study of free

jazz that, unlike many post-situationist critiques of music in toto

as an alienated commodity, spends much time describing how music as a

social-historical practice and a theory-in-action, has political import

beyond theses and manifestos. In this book the musiking of Ayler,

Coltrane, Sun Ra, et al, is reclaimed as a ‘living labour’ with sonic

matter: “Free jazz is characterised by an emphasis on political

signalisation […] but its militant status is especially clear in that the

contradictions between varied cultural codes, music materials and multiple

historical traces at work in the music.”[4]

Free jazz as a melange, a bricolage, is also a key building block within the

French Underground whose bands and ensembles, in Thompson’s words, often

exhibit a “lack of chordal foundation.” It is this athematism, avoiding the

compositional strictures of harmonic song-structures, that enables the

inclusion of ‘varied cultural codes’ and a setting of these in parodic and

challenging juxtapositions. This collage-effect, then, also bears a

relationship to the Situationist cultural practice of détournement as

the re-routing of existing materials that brings social contradictions to

the fore. A key exemplar of this is described by Thompson in relation to Red

Noise. He cites group-member Patrick Vian: “I wanted our music to be a kind

of rubbish bin: we threw in scraps of popular songs, noises, anything,

stirred it all up, and dished it out as it came. We wanted to demolish, to

throw everything away. If others want to reconstruct afterwards, that’s

their job, not ours.” This band, formed in live jam sessions in the

courtyards of the occupied Sorbonne, only ever recorded one album and that a

belated release that did little to capture the “sonic madness” of their

performances which, in the words of member Patrick Vian, were intended to

“exteriorise the internal rebellion” of their audiences. As Thompson notes,

the opening to this album is a détournement of the French chanson

and ya-ya styles as these give rise to a parody of Anglo-American

rock. These styles are mocked with the toilet-humour of the lyrics

(introduced by the sounds of someone taking a pee) before venturing into a

long meta-categorical track. This track, titled ‘Sarcelles is the Future,’

could also be seen as echoing the early situationist interest in ‘unitary

urbanism’ as Sarcelles was a one-time impoverished Paris suburb that

appeared in the future as a gentrified zone.

A

cornerstone of Situationist ideas was what they polemicised as the

‘revolution of everyday life’ (more or less taking a cue from PCF renegade

Henri Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life). Capital had come, as

Thompson writes, to make “everything tradeable into a commodity,” and

opposition to this, as it extended to the formerly untradeable, was

reflected in a manifesto issued by ‘Force for Liberation of and Intervention

in Pop’ (FLIP): “From now on Pop will not simply be a product of greater or

lesser quality, it will be the vehicle of our revolt against the old world.

It will be a subversive weapon to change life and transform the world right

here, right now, everywhere that struggles are carried out: in offices,

workers hostels, suburbs, council estates, schools, universities etc...”

Thompson notes that the groups gathered under this banner (including

Komintern, Red Noise and Fille Qui Mousse) jammed en masse from a

flat-bed truck in the midst of a demonstration gathered to celebrate the

centenary of the Paris Commune. However, this umbrella grouping was short

lived and not simply as a result of the weight of its own polemic but at the

hands of attempts to hijack it by Maoist groups like Gauche Prolétarienne

(who counted J.P. Sartre as a one-time member). One more attempt was made to

rhetoricise the import of underground culture with the ‘Rock Music

Liberation Front’ who perhaps put into plain phraseology the Situationist

maxim of ‘realising and supressing art’ in the everyday when they wrote:

“Music as a separate form will be dissolved into the lived experience of

everyone.”[5]

As

musician, Dominique Grimaud, offers, these shortlived attempts at explicit

politicisation left their traces, but what is intriguing is that discursive

practices like these weren’t concertedly pursued again until ‘The Rock in

Opposition’ movement came to life in 1978 (formed by Henry Cow it included

French bands like Art Zoyd and Etron Fou Leloublan). The clues for why this

happened are scattered throughout this book. There is not just the risk of

loose collectives and their pulling-power being instrumentalised by the

Maoists (“Pop for the People”) but a growing sense that the music itself –

its practice, its reception contexts and its awakening of

desiring-perception – was a politicising factor that had no need to take up

theoretical positions that could be recognised by the prevailing political

doxas. The wilful proffering of intense musical experience by these bands

(which perhaps unites them beyond genre distinction) had ramifications for a

musically inspired coming-to-consciousness that, in face of the surrounding

cultural and political conditioning, has, as Tim Hodgkinson argues, an

ontological power: “Music is sounded between persons […] it activates that

space as a dynamic ontological environment in which the listening subject

comes to life.” This echoes Vian’s hopes for music-making as being able to

‘exteriorise internal rebellion’ which is tantamount to a rearticulation of

the individualised person as a mode-of-becoming, that, as Hodgkinson adds

“catalyses a new ontology for the political subject.”[6]

What comes to life is a (listening) subject that is enabled to recognize its

conditioning and from there embark on the process of overcoming the ways and

means that it has been produced as an homogenous subject (homo economicus).

Again, it is Vian that intuits this shift away from the ‘revolutionary

subject’ of the working class and its organizational forms to the

‘subjective revolution’ (the personal is political) heralded by the post-68

profiling of a dis-alienating psycho-politics and its sense of

gemeinwesen: “Revolutionary songs have been sung for a thousand years,

and the revolution doesn’t look like it’s coming closer. We have to try

something else...”

In

a way Thompson’s book documents and gathers testimony of this ‘something

else.’ The depth and breadth of the bands and outfits that come into a

first-time focus here make this underground scene (and others like it, such

as the various punk scenes that followed it) more like a movement than an

easily policed niche. This was a movement that eschewed politics proper for

a micropolitics (and here we, in part, mean a politics of the senses in

Marx’s terms[7])

that brought desire/pleasure and its vicissitudes to the forefront of any

revolutionary rearrangement: the ‘permanent play’ and ‘experimental

behaviour’ that the early Situationists vouched for, and which the bands

covered here seem to be enacting, is a means of resisting the reductive

power of a spectacle that, to draw on R.D. Laing, encourages us all to

perceive and feel the same thing.[8]

The French underground’s turn towards a politics of experience comes to

challenge the knowledge-based politics of the traditional Left and, more

importantly, looks for other communicative forms than those that, with their

dogmas and hierarchical orderings, lead to the reiteration of what amounts

to standardised forms: clichéd riffs and antique slogans. These latter,

being self-explanatory and self-evident amount, in the words of Hodgkinson,

to the “shared nonthought” of the spectacle (and its self-objectifying

musical avatars) that encases us in consumer demographic identities and the

“normal grammar of agency” otherwise known as passivity.[9]

If

the festivals as mass gatherings were one form that enabled new forms of

socialisation, then another was that of communal living. As with many

free-jazz acts that can be more aptly described as ensembles (following

through from the big band form) than groups or combos (the rock four-piece

etc), the French groups discussed here often took on the form of

multi-membership and, as with jazz players, a crossing over between groups

with sub-ensembles of players forming often for only one session. Thompson

draws our attention to how musical practices gave rise to communising

practices that, whilst rarely successful, indicate a desire to ‘live’ the

music and extend its import into everyday life. Does musiking in this

way become what the SI referred to as an ‘experimental behaviour’? The

recasting of a post-68 revolutionary practice (with music no longer figuring

as a side-line agit-prop) begins to concern itself with seeking out new

forms of life (ontological dynamism) and endeavouring to practice that ‘open

creation’ which Jorn, back in 1960, offered as a “homeomorphism, variability

within a unity.” The SI with its exclusions, with its eventual membership of

one, may have given impetus to underground music as politicised but, despite

innovations like ‘constructing situations’ and ‘the realisation and

suppression of art’ it did not heed Jorn. The groups featured here, with

their metamorphosing sonics and temporal scramblings, with their

incorporation of non-sonorous forces and exogenous elements, not only made

audible a sociate sound, but tried to extended their “instant composition”

to the ways and means of living together. That these often fail may, in

reference to the SI, be as much an issue of the autonomisation of an

affectless discourse that takes no heed of the power-of-becoming that

inheres in music.[11]

[1] The title of this

review-article is the name of a musical outfit that comprised of

Jean-Jacques Birgé,

Francis Gorgé,

and Shiroc. They took an impetus from employing cinematic techniques

in their music: “montage, ellipses, close-ups, perspectives.”

[2] See Roger Sutherland, ‘The

Death of the Scratch Orchestra: A Personal Account’, Noisegate

No.8 2001. ‘Musiking’ is a term developed by Christopher Small to

describe music as a social-relational open dynamism. To date, The

Scratch Orchestra appear on vinyl just once and that a posthumous

(and controversial) archive release: Live 1969 (Die Stadt,

1999.) An incarnation of the Scratch collective performed at Café

Oto, London in February 2015. See

https://www.cafeoto.co.uk/events/nature-study-notes/

[3]A rare indication of music

being taken seriously by any Situationist is Asger Jorn’s

collaboration with Jean Dubuffet on Musique Phénoménale

in 1961. This was recorded under the auspices of an Italian art

gallery after he had amicably quit the SI.

[4] Philippe Carles & Jean-Louis

Comolli, Free Jazz/Black Power (1971), University Press of

Mississippi 2015 p.278. One or two passages of this book seem

resonant with Debord’s concerns and style (including italicisation.)

In talking of the “critical occupation of jazz” by mainly white

middle-class music critics the authors write “Completely hiding

social and racial determinants was impossible, so they were instead

posited modestly, from a sociologist’s point of view, as a kind

of backdrop that explained nothing because it explained too much.”

See p.49.

[5] In a similar vein, Luc

Ferrari, a pioneer of environmental found sound, sonic collage and

musique concrète,

once offered: “The concept of music will need to disappear… it is

too specialised and I believe our thinking is involving away from

specialisation.”

[6] Tim Hodgkinson, Music and

the Myth of Wholeness: Toward a New Aesthetic Paradigm, MIT

Press 2016 p. 163. John Coltrane points towards this ontological

dynamism in musical experience when he says: “I think that music is

an instrument. It can create the initial thought patterns that can

change the thinking of people.” Cited by Carles and Comolli, ibid,

p.175.

[7] Marx: “Man is […] affirmed in

the objective world not only in thought but with all the

senses.” See Early Writings, Pelican 1975, p.353. Earlier in

this passage Marx writes that “the senses have become theoreticians

in their immediate practice.”

[8] See ‘Did you used to be R.D.

Laing?’ at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIih_3KgwIU&list=FLkYNWzbjl-VaiyJO1RkTyCg&index=95

[9] See Hodgkinson, ibid

pp.162-163.

[10] Archie Shepp’s set in

Algiers opens with the track ‘We are back’. At the outset,

surrealist poet Ted Joans intones “We have come back/brought back/to

our land Africa/ the music of Africa/Jazz is a black power…” There

is something redemptive in this, a return of the sons and daughters

of slaves who are wielding the re-activating power of hidden

history, a history of suffering and feeling contemporised through

the channelling medium of the intensifying music of free jazz.

[11] The fetishization of

coherent theory with its attendant “authentic rationality” (Debord:

Sick Planet) can act as a block between people by disavowing

the spectra of consciousnesses and hence reducing the possibilities

of inter-subjective communication.