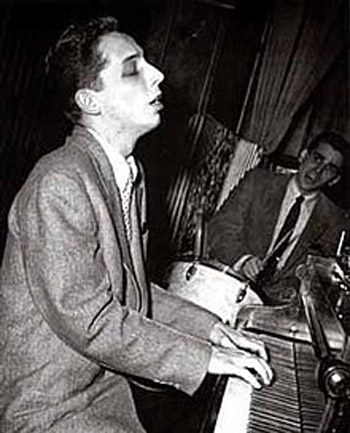

A DEATH IN PARIS ; THE

SAD CASE OF DICK TWARDZIK

Jim Burns

On the 21st October, 1955, a group of musicians gathered in a

Parisian recording studio. They included trumpeter Chet Baker, bassist Jimmy

Bond, and drummer Peter Littman, all members of a

quartet Baker had brought to Europe. The Swedish baritone-saxophone

player Lars Gullin was also present, but missing was pianist Dick Twardzik.

After an hour or so it was decided to telephone the hotel where

Twardzik was staying to ascertain if he had left for the studio. When the

manager failed to get a reply from Twardzik’s room he gained access and

found him dead, with a hypodermic needle still in his arm.

He had overdosed on heroin, and was

just twenty-four when he died.

Those appear to be the facts, though somewhat different accounts appeared in

print over the years. One said

that Jimmy Bond was sent to the hotel to find out why Twardzik had not come

to the recording session. Another that it was Peter Littman who went. Later,

there were suggestions that either Baker or Littman, or perhaps both, had

been with Twardzik when he overdosed, and had left, not wanting to be

involved in likely difficulties that might arise. All three were heroin

addicts, though Baker in later interviews often claimed not to have been at

that stage in his career. Bond was the only one not using drugs, and when

the group had been touring in Germany and Holland, prior to arriving in

Paris, he had taken on the responsibility of looking after Twardzik whose

behaviour could at times be unpredictable. He had more than once passed out

due to the effects of narcotics.

Richard Twardzik was born in 1931. His father was an artist, known in the

Boston area, and was skilled at designing stained glass windows. His mother

also had artistic inclinations, and was a scientific illustrator at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Together

they supplemented their income by breeding award-winning German Shepherd

dogs. Their son, an only child, was something of a young prodigy as a

pianist, and made his professional debut at the age of fourteen. He had been

trained in classical music, but when he heard the new jazz sounds of bebop

in the late 1940s he moved in that direction and soon began working with

jazz groups. This was a period when heroin use was prevalent among many

modern jazz musicians, and Twardzik seems to have started injecting it in

his late teens. There’s no doubt that he was firmly addicted when he went to

Europe with Baker.

It’s not my intention to provide a full biography of Twardzik, but it is

important to say that in the early-1950s he worked in clubs with Charlie

Parker, Serge Chaloff, Sonny Stitt, and Allen Eager, all of them key players

in the modern movement. And in 1954 he was considered good enough to record

under his own name for the Pacific jazz label with a trio that included

Peter Littman on drums. Twardzik had an idiosyncratic approach to the piano

in that he was influenced by the leading bop pianist, Bud Powell, but also

incorporated some aspects of contemporary classical music into his playing,

and not just in terms of throwing a few quotes from Stravinsky and others

into his improvisations. His method of constructing a solo moved away from

simply following a chord sequence or a melody, and deviated into patterns

that seemed to subtly alter the rhythmic base, though the jazz impulse was

always in evidence. Trumpeter Herb Pomeroy said : “He understood classical

literature and he swung so hard. He understood Bud Powell and Thelonious

Monk. Harmonically he was a combination of the most advanced bebop of the

day and 20th-century classical music”.

Some of the music played by the Baker group at concerts in Europe was

recorded and released on LPs and CDs in later years. And the group made

studio recordings in Paris which featured Twardzik and were issued at the

time. His solo playing was never less than good, and sometimes much more

than that, though comments have been

made to the effect that Twardzik may have been “too individualistic in the

rhythm section”. Reviews sometimes related Twardzik’s style to that of Dave

Brubeck, probably because both had a grounding in classical music.

Close listening, however, indicates that there were clear

differences, with Twardzik having a looser, more open approach to

improvisation and, I would suggest, a more natural swing feeling.

The Paris studio sessions took place on the 11th and 14th

October 1955, and Twardzik died on the 21st. When Baker recorded

again on the 24th a French pianist, Gerard Gustin, had replaced

Twardzik and the Swedish drummer Nils-Bertil Dahlander had taken over from

Littman. Jimmy Bond soon returned to America, as did Peter Littman.

According to Jack Chambers, Twardzik’s biographer, both eventually

settled in Los Angeles, though not establishing careers in the music

business : “Bond became a successful realtor and played his bass

sporadically; he showed up occasionally in pick-up bands.......Littman

disappeared. Baker’s biographer, Jeroen der Valk, heard that he was serving

gas in Los Angeles in the 1990s, but could not track him down”.

Littman’s drug addiction (he was

just twenty years of age) could have affected his ability to work regularly,

but there may also have been doubts about his capabilities as a drummer. In

the summer of 1955 the pianist John Williams had been offered a job with

Baker and went to Birdland to listen to the group: “Littman was terrible.

And since everybody in Charlie’s (Tavern) knew everything about everybody in

those days, I knew he was a lost-cause junkie. I had assumed, as did most of

the guys, that the junk was the reason Chet had him on the band. It

certainly couldn’t have been for his playing”. Williams turned down the job.

As an aside, it’s interesting to reflect that, had Wiliams decided to join

Baker, he might have been the group’s pianist for the European tour. Another

pianist, Russ Freeman, who had been working with Baker in clubs and on

records, had also been

reluctant to leave America. Like Williams he had doubts about Littman, both

as a drummer and a junkie. He

referred to him as “a sycophant, a young punk, sort of creepy”.

I’ve only dealt with the brief period that Twardzik was with Chet Baker and

he had wider experiences in the few years he was active in jazz. The

biography by Jack Chambers provides an

account of his life and music, as does James Gavin’s book which

supplies more personal information. Dick Twardzik had a lot to offer, and

may have progressed to greater things had he not died in tragic

circumstances.

BOOKS

Bouncin’ with Bartok : The Incomplete Works of Richard Twardzik

by Jack Chambers. The Mercury Press, Ontario, 2008.

As Though I Had Wings : The Lost Memoir

by Chet Baker, St Martin’s Press, New York, 1997.

Deep In a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker

by James Gavin, Chatto & Windus, London, 2001.

RECORDS

Chet Baker Quartet : Koln Concert featuring Dick Twardzik.

RLR 88618.

Chet Baker Quartet: Jazz at the Concertgebouw.

Dutch Jazz Archive Series NJA 0701.

Chet in Paris: Featuring Dick Twardzik.

Emarcy 837474-2. The studio recordings.

Lars Gullin with Chet Baker.

Dragon DRCD 2324. Some tracks are from a concert in Stuttgart. and feature

Twardzik.

Dick Twardzik Trio : Complete Recordings,

Lonehill Jazz LHJ 1-0120.

Jay Migliori and Dick Twardzik Jazz Workshop Quintet,

Fresh Sounds Records FSR-CD 989.

I have listed this even though it does not relate to Twardzik in

Europe. It was recorded at the Harvard WHRB radio station in May 1954 and is

an example of him on his home ground of Boston. Tenor saxophonist Jay

Migliori was a student at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, snd would

later be a member of Woody Herman’s band.